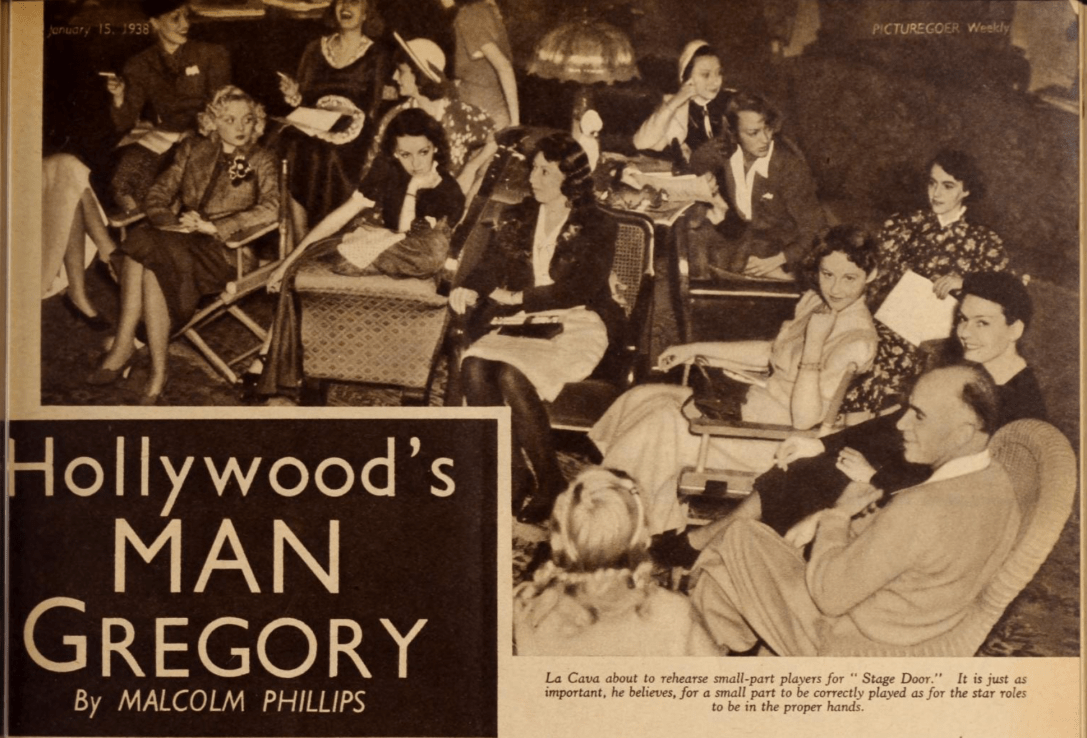

The La Cava method reaching across the waters! Picturegoer published this fascinating little article about Gregory La Cava and the production of Stage Door (1937) in their January 15 1938 issue. A few things of note, it is interesting that, at the time, there was this issue of ascertaining what La Cava’s unique style actually was, and I think it’s interesting that Malcolm Phillips uses Frank Capra in comparison to La Cava. Anyway, it’s an interesting article I have transcribed the interview below:

Gregory La Cava is a name to conjure with in films to-day. He is one of the few movie directors with the Midas touch. Here Malcolm Phillips tells you something about the man who made “Stage Door” and some of the inner history of that Hepburn-Rogers picture.

It is the “thing” in the film colony these nights to attend the concerts in the Hollywood Bowl. Stokowski and Heifetz draw huge audiences. Lily Pons, by far the greatest singer of all the prima donnas who have come into pictures, set up a record when she sang there the other evening. For all its recent dizzy ascents in the realms of the highbrow, however, the music that Hollywood still likes best is the merry tinkle of the coins as they roll into box-office cash boxes. Names make more than news in movie-land, they make money. That is why stars are paid $30,000 a picture. Producers sign their cheques cheerfully. If that was the principal worry of film-making they would have fewer grey hairs. Stars are important, but, as more than one temperamental young lady has discovered, not indispensable. They are like “buses, there will always be another along in a minute. Provided, moreover, that they have the precious gift of personality, they can be developed quickly. Katharine Hepburn, Robert Taylor, Tyrone Power and, more recently. Wayne Morris, jumped into the big money almost overnight.

The other essentials of profitable movies are not so easy to come by: Directors, for instance, cannot be made by a little experience and a lot of ballyhoo. It takes them years to learn their jobs. And after that most of them are merely competent hacks. Dorothy Arzner the other day assessed the minimum period in which anyone could master the technique of him directing at ten. And even those years with the divine spark have to know the mechanics before they can make good movies: Any producer would swap half a dozen stars for one director who could be relied upon, given the raw materials in the way of a reasonable script and cast, to turn out good pictures.

There are fewer than you might imagine. Most of Hollywood’s directors are successful only with fool-proof scripts and strong supervision. It cost the British film industry a lot of money to find that out in the last few years. Directors, imported here on the strength of American reputations, have, with one or two exceptions, proved hopeless without the Hollywood machine behind them.

There are probably less than a dozen genuine box-office directors in films today. Frank Capra, who has been of greater value to Columbia than the studios entire star roster, is one of them. “Woody” Van Dyke, of M.-G.-M., is probably another. Capra’s greatest rival, however, as the director with the Midas touch, may very well be Gregory La Cava. If not yet quite the miracle man that Capra has proved himself in the last year or two, La Cava has run him very close.

He has, unlike Capra, not been closely identified any one style of film. He first attracted notice as a front-rank director in the movingly human Melody of Life. Since then he has scored with such widely divergent themes as the whimsical What Every Woman Knows, the melodramatic Gabriel Over the White House, and the psychologically heavy Private Worlds.

His sure flair for comedy in She Married Her Boss was well up to the Capra standard, while with My Man Godfrey he created a film fashion that is still with us. The majority of these pictures (one might almost say with the exception of Private Worlds, hardly a popular subject, all of them) were money spinners.

My Man Godfrey, in addition to starting a vogue, created a £30,000-a-picture star out of Carole Lombard. My Man Godfrey, moreover, was la Cava’s film from start to finish. With Capra’s work one always has a suspicion that Robert Riskin was looking over his shoulder. Gregory La Cava is the only director who makes up his pictures as be goes along. William Powell told me recently how La Cava himself improvised the best of My Man Godfrey on the set.

Though extremely thorough in preparation, La Cava is a firm believer in the extemporaneous technique, Lubitsch has every scene worked out to the smallest movement and gesture before he steps on a set. La Cava prefers to start with a general idea of a scene, and work it out on the spot. He usually goes on the set without a line of his dialogue written and often with no notion of how a scene will end. This method, he declares, permits the director and scenarist to adjust the dialogue directly to the people who have to speak it. That explains the spontaneity of much of his work. Yet few directors emerge from the set with more compact, cogent, and polished footage.

Some actors, of course, strongly resent this haphazard method of approach, but they usually come to like it in the end. Powell himself, who studies his lines more carefully than anyone in Hollywood, and is a great stickler for the written script, took violent exception to the La Cava technique in the case of My Man Godfrey and flatly refused to work that way.

“Well, we just went along.” says La Cava, “for several days, making the best of it Then we came to a scene for which it just happens we had written lines a week in advance. Bill had been studying them diligently–but when we started to shoot the scene he forgot them altogether! From then on he thought my idea was swell.”

Katharine Hepburn and Ginger Rogers readily fell into La Cava’s way of doing things in Stage Door, also put into shape on the set. For one thing Stage Door, though a hit play, could not be adapted to the screen without considerable alteration. The play deliberately set out to prove, as La Cava puts it, “that Hollywood isn’t a combination of Mecca and El Dorado, and that all successful people there are platinum blondes without any talent.”

“I’m doing pictures for picture audiences,” he adds, “so I had to take a different point of view. Also I had the problem of making a film with two stars––not one, as was the case in the play. This affected considerably the type of story––which, I must admit, was just a general idea when we started production.”

Incidentally, La Cava was the subject of considerable commiseration when Hollywood heard that he had got the assignment. The tempestuous Katharine Hepburn, the pointed out, had never been teamed with another feminine star. And with another redhead, too!

The picture started production to the accompaniment of rumours of verbal fireworks and predictions of physical hair pullings. Hepburn had said that she was glad that Ginger Robers was to be ingenue in her picture. Hepburn had protested to the front-office about the magnificence of the wardrobe allotted to Ginger Rogers. And so on, and so on.

“Almost every star I have ever worked with,” says La Cava, “has been recommended to me secretly as being extremely difficult to manage. Nut I have found that so-called temperament is just a higher form of intelligence.”

“Screen stars who do not possess the emotional fire sometimes labelled artistic temperament aren’t worth their salt. Nice girls as we know the type are rarely good actresses.”

Just as he created a brilliant new comedienne in Carole Lombard with My Man Godfrey. La Cava has, with Stage Door, given us a new dramatic actress in Ginger Rogers. He doesn’t take any credit for the fact; he is a great admirer of Ginger’s talents. “Ginger Rogers,” he says, “has everything.”

His pet scene in the picture is that in which Gigner, broken-hearted, enters Katharine Hepburn’s dressing room on the opening night of her first play and accuses her of responsibility for the suicide of a friend.

“In this scene, he thinks, “Miss Rogers has proved that she is an actress of great emotional range.”

And never,” he adds, “have I heard a finer tribute paid to a performer than was spoken by a cameraman right after Ginger had finished that scene. “We had all been greatly moved by her performance and there was an uncommon hush over the set. I know that I for one had tears in my eyes. “Then I heard this cameraman, standing close beside me, speak in a matter-of-fact voice to no one in particular-just sort of thinking out loud And what he said was simply, ‘Throw away those dancing shoes.””

Gregory La Cava is some years older than Capra––he is 45. He was born in Towanda, Pennsylvania, and his original ambition was to be a great painter. He studied and practised art for fifteen years, before financial reasons forced him into the commercial field. He was a cartoonist on the New York Globe and the New York Evening World. He came into films as an artist, and was one of the pioneers in the animated cartoon field. Among his work was the animation of the early Mutt and Jeff cartoons.

His old profession proved useful, incidentally, during the production of My Man Godfrey. Back in 1930, the director attended a week-end party at Malibu Beach, where a lanky, sad-eyed Russian chap convulsed the guests by giving a burlesque of a gorilla leaping from branch to branch, using the furniture as his forest. Gregory wrote in his notebook, “Mischa Auer, a natural comedian frequently miscast in film tragedies. Use him in comedy some day.”

Six years later, when he received the script of My Man Godfrey, La Cava recalled The actor’s clowning and decided it would fit perfectly into this mad and merry movie. But Auer’s film test proved disappointing. What had seemed so funny in the parlour was flat on the screen. It was then La Cava went back to his old job of cartoon animator. He sent for a pad of white paper and propping it against his knee for an easel, he drew a sequence of 43 comic monkey postures and gyrations. Then Auer practised each successive bit of business in the sequence of these lightning drawings. His second test was perfect, since by rehearsing from the pencil pictures, he was able to get proper timing and cinema continuity into his actions which previously had been too fast and scattered for the camera to follow.

From miniature cartoons La Cava went on to become a scenarist for Lloyd Hamilton and Jack White. Later he wrote the screen adaptations for the Johnny Hines “Torch” series, and then became a Mack Sennett comedy director, and, like Capra, graduated from slapstick to drama. That varied background probably explains his extraordinary versatility. Off the set he is one of Hollywood’s most expert practical jokers On it, he has one particular whim. In all his films he has music played at all times between shots to match the mood of every scene.

However, music, unique methods and all, Gregory La Cava is one of filmland’s few Directors with the Midas Touch