I’m still slightly frazzled from having introduced Gregory La Cava’s Unfinished Business at the BFI last Friday for the Film on Film Festival. I can’t thank Senior Curator of Fiction James Bell enough for giving me the opportunity to do so, and the great projectionist team for screening the film. I thought I’d write a post to follow it, as whenever I hear an introduction for a film I’m always curious myself to where certain information was obtained and the chance to hear about it in more detail as I was, as mentioned, frazzled and there are mountains of fascinating accounts and notes behind each La Cava film, and Unfinished Business is no different.

The line I always think about and associate with Unfinished Business and La Cava is “You can’t make an eagle out of a hen by changing the shape of the egg.” That mixture of odd and frankness seems to sum up La Cava perfectly, and probably one of the many lines held in La Cava Script Supervisor Winfrid Kay Thackrey’s loose-leaf binder. It was wonderful to be at the BFI and to introduce one of La Cava’s best and, unfortunately, rarely screened films. Unfinished Business breathes in a way that you would not expect in reading an outline of a story of a small-town woman moving to New York to pursue a dream in singing, but along the way gets romantically entangled with two men. Whenever I watch the film I’m always slightly stunned by the lack of that complete naivety associated with the type of character Irene Dunne plays in the film, and whilst she is lovestruck to a certain degree there’s still this very adult wariness to her character and the lack of achieving her operatic dreams.

The film evolved from this idea that Vicki Baum created, which Kay Thackrey writes remains in certain characters, but little of Baum’s work remains after La Cava brought back one of his closest writers and friends, Eugene Thackrey. Here is Kay Thackrey’s words on the production of Unfinished Business in her 2001 memoir Member of the Crew:

“Unfinished Business, as the picture would be called, went together wonderfully well. Gene and Greg worked easily together. It was something of a game to top each other. My notebook filled and refilled. Gene was a pacer; he paced back and forth in the window space of Greg’s big social room. Movement seemed to create witticisms. Greg joined, replaced a phrase, one line brought on another, a statement brought forth a question or suggested a situation they both leaped on with enthusiasm, two frogs snapping at the same fly. There was good deal of laughter. A scene was built to a climax. “Great,” Greg would exclaim. “Find a place for it, Wini.” Sometimes it was crossed from my pages as a “doesn’t fit the character,” or “too far afield,” but the sense of it frequently lingered and would suggest another situation, another location in my loose-leaf, another character. A half-hour of “what ifs” from either or both men might follow. Loose construction that could move several directions, building up or tearing down a whole segment, which often was then dropped because it wasn’t worth so much destruction.

Vicki Baum, the great dramatist of Grand Hotel, had created an earlier character both Greg and Gene liked. She was back in the pages, dropped and returned a half-dozen times. Finally she came back and remained, expertly played by sparkling little June Clyde. A character Gene brought to life, later to be played by Eugene Pallette, was a rotund butler who in trying on his World War service uniform, found it didn’t quite fit and declared, “It’s shrunk!”

Greg found characters and dialogue to keep his stock company alive— actors such as Samuel Hinds, Walter Catlett, Esther Dale, Kathryn Adams, Norma Boleslavski-and he generously gave Gene solo credit for the screenplay, which was particularly important when the picture went on to win an award as one of the ten best of the year.”1

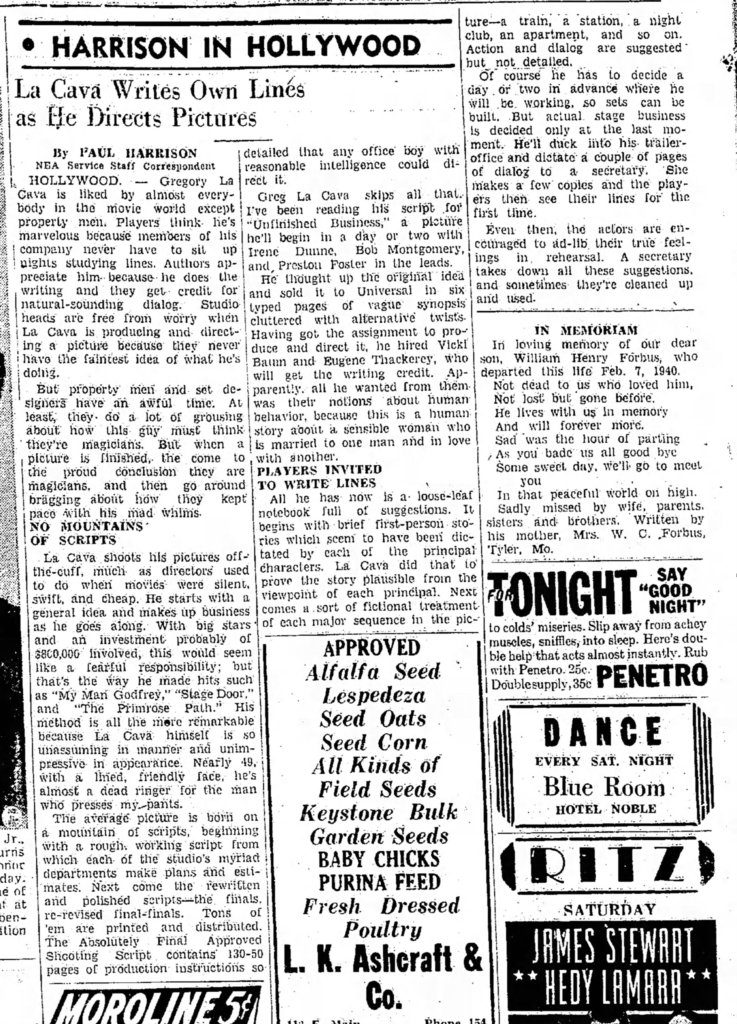

“When Unfinished Business began shooting at Universal Studios, Claire Huntington Glen went to work for La Cava as his office secretary. My work was in the camper that moved from stage to stage as the picture progressed. I was there to work on the story. As always, we had a detailed synopsis, then pages and pages of dialogue, along with individual scenes evolving between characters as they were talked through by La Cava and Gene in those weeks of preparation, but most of these fragments lacked placement. They could live on the train, in the living room, the café, even in the opera house, and many would never find a home. Each opening scene was written at the beginning of a shooting day, the contribution of both men, quickly typed, with many carbon copies, and distributed by me to the actors. Pages were selected from my loose-leaf binder during dictation, amusing lines approved by La Cava or thrown away, other lines substituted as characters developed or began to drift into obscurity.”2

“At night when we finished shooting, there was always a group La Cava would invite to his bungalow for drinks. Claire, Johnny Jones, and I occupied the outer office, where each of us had our own typewriter and our own duties. The assistant director, too, had offices in the same bungalow. In between typing a rough draft for the next day’s dialogue I kept glasses filled in Greg’s office. W C. Fields would be there, Gene Thackrey, Leo McCarey, Joe Valentine-our cameraman-and many others, old friends who happened to be shooting on the lot and were invited to stop by. I typed the production sheet, handwritten at the end of the day by the assistants, giving all departments the information they needed for the next day’s shooting: the stage on which we would work, the time of shooting or of moving from one stage to another; what actors were called and at what times; the costume number for each actor; the scene numbers; and a wealth of information needed by carpenters, set dressers, animal handlers—if we were shooting outside transportation, camera, sound, wardrobe, electricians. As nearly as possible all this information was finalized during the day over the phone by the first or second assistants. The production report was for-the-records. On the usual motion picture, this planning work was done by the assistants and production persons before actual shooting began, but with La Cava this was not possible. We had only a general idea of what we would be shooting, where, and when. The story itself was just an outline, not a completed script broken down into specific locations and given specific numbers. But we always knew at the end of each day what we would be shooting the following day, and even though this may have been short notice for many departments with heavy schedules for other pictures as well as ours, it worked out very well for La Cava. He simply did not know how his actors would react to each other until they had played out the beginnings of their story together.”3

Unfinished Business is perhaps the most concerned with real human experience out of La Cava’s films, and the opportunity to see it on the big screen with a 35mm print was a treat. As you probably know, screening of his work outside of My Man Godfrey and Stage Door is, unfortunately, rather rare. In my introduction I mentioned how La Cava’s reputation rests in those screwball comedies of the 1930s, and it’s true that Unfinished Business contains similarities with La Cava’s prior films, but there is a definite tonal change, perhaps due to the war, that defines Unfinished Business against La Cava’s previous work and the potential if his health hadn’t declined.

It does still surprise me, that La Cava is not as remembered as his peers such as Frank Capra, Leo McCarey, and Preston Sturges are. Speaking of Capra, it touches me that Capra remembers La Cava in his memoir, he wasn’t part of La Cava’s group of friends, and still reveres La Cava’s methods to be fresh and unique forty years on:

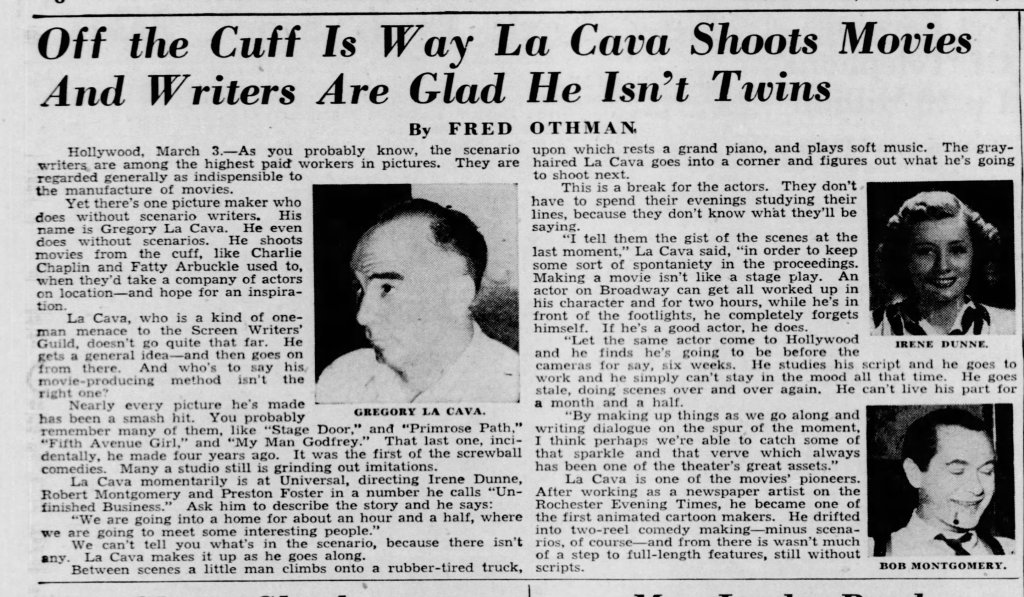

“All directors must ponder and meditate in their own way. For they all have this common problem: keeping each day’s work in correct relationship to the story as a whole. Scenes shot out of time and context must fit into their exact spot in the mosaic of the finished film, with their exact shadings in mood, suspense, and growing relationships of love or conflict. This is, as one can imagine, the most important and most difficult part of directing, and the main reason why films, perforce, are the director’s “business.” The meteor Gregory La Cava (Symphony of Six Million, Stage Door, My

Man Godfrey) was an extreme proponent of inventing scenes on the set. Blessed with a brilliant, fertile mind and a flashing wit, he claimed he could make pictures without scripts. But without scripts the studio heads could make no accurate budgets, schedules, or time allowances for actors’ commitments. Shooting off the cuff, executives said, was reckless gambling;

film costs would be open-ended; no major company could afford such risks. Films are a peculiar dichotomy of art and business, with executives emphasizing business. But not La Cava. He stuck to his off-the-cuff guns. Result: fewer and fewer film assignments for him-then none. The flashing rocket of his wit was denied a launching pad because he wouldn’t, or couldn’t, conform. So he mixed his exotic fuels with more mundane spirits, and brooded himself into oblivion-his rebel colors still flying. La Cava was a man out of his time—a precursor of the “new wave” directors of Europe.

Pity he didn’t live long enough to lead them.”4

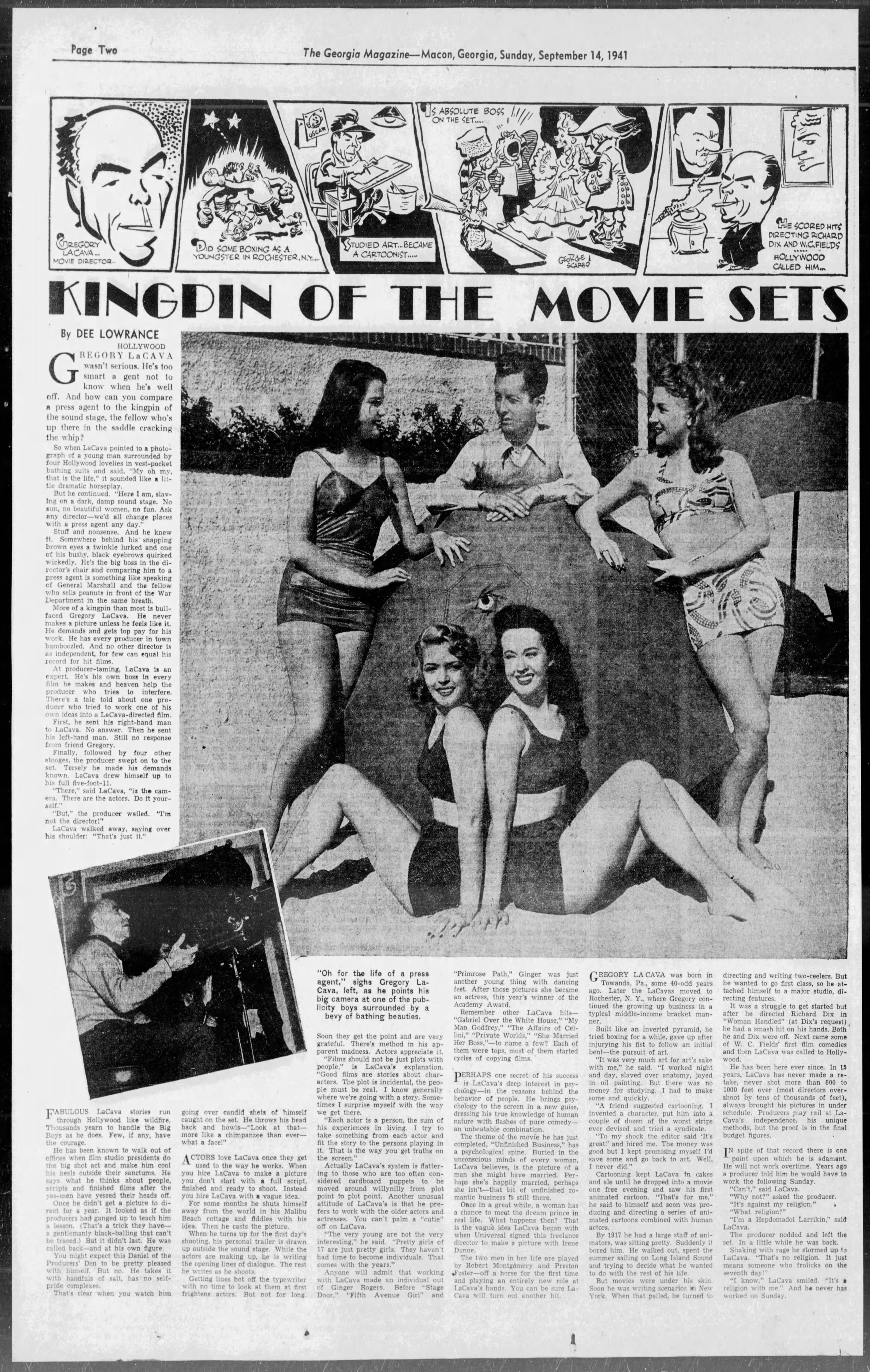

La Cava as a “man out of his time” was definitely expressed at time, as on the release of Unfinished Business, La Cava’s own idiosyncrasies were as of interest to the public as the work he was making. La Cava is best known for his particular interest in capturing the human experience and the actors’ personalities, incorporating overheard conversations into the script, and encouraging his actors to improvise in rehearsal and scene, as Katharine Hepburn and Pandro S. Herman remembered regarding Stage Door (1937) in a series of interviews for the 1987 documentary about RKO. Improvisation was not a new thing, nor was it unusual in silent film, and with fellow directors such as McCarey, but his particular interest in incorporating the actors themselves into the characters was particularly unique. Studios and press capitalised on La Cava’s own “Lubitsch Touch”, with attempting to ascertain through interviews what his method was. The human principles or “psychological spine”, as Dee Lowrance described in an interview with La Cava regarding the film5 to his films is in La Cava’s interest in improvisation and studying his actors. La Cava described himself as a bit of a psychologist, by his interest in studying people, with his “touch” being an off-the-cuff “go-as-you-please method” in a 1938 interview for Collier’s magazine that I wrote about in a previous blog post. Not only are the actors interwoven, but La Cava is too deeply embedded in his work, and Unfinished Business is no different. La Cava’s own struggles with alcoholism taking play in Robert Montgomery’s Tommy Duncan. Duncan’s alcoholism doesn’t serve primarily as comedic relief but rather more a moralistic reflection of La Cava’s struggles and the effect on the people around him. Alcohol and the liberation and trappings of it feature in many of La Cava’s films, from his animation to silent and sound work, but it is in Unfinished Business where there is a rather frank reflection on La Cava’s afflictions.

Here are some interviews and articles from around the release of Unfinished Business. You see La Cava’s off-the-cuff method of improvisation is focused on in a particular detail by this point of La Cava’s career:

Unfortunately, in later interviews with some of La Cava’s stars, his name is rarely brought up, so I have yet to encounter Robert Montgomery or Preston Foster’s thoughts on working with La Cava, but we have James Bawden to thank for asking Irene Dunne about working with La Cava and her opinion on his methods. In a 1974 interview later published in Conversations with Classic Film Stars: Interviews from Hollywood’s Golden Era, Bowden relayed Ralph Bellamy’s recollections on working in La Cava’s subsequent film, Lady in a Jam (1942): Ralph Bellamy once told me in Lady in a Jam [1942] you lost your legendary cool. DUNNE: Can’t a girl have at least one nervous breakdown on set? I’d done Unfinished Business [1941] for Greg La Cava and it had turned out half okay and I foolishly agreed to this one. He said he’d shoot it in the McCarey style—i.e., there was no real script. We’d improvise. We shot in Phoenix and it was very hot. There was no air-conditioning then. And I sweltered in my portable dressing room for ten weeks as Greg waited for inspiration and it never came and finally I just threw things around and it turned out to be a real disaster and Greg only made one more movie after that and it was five years later.

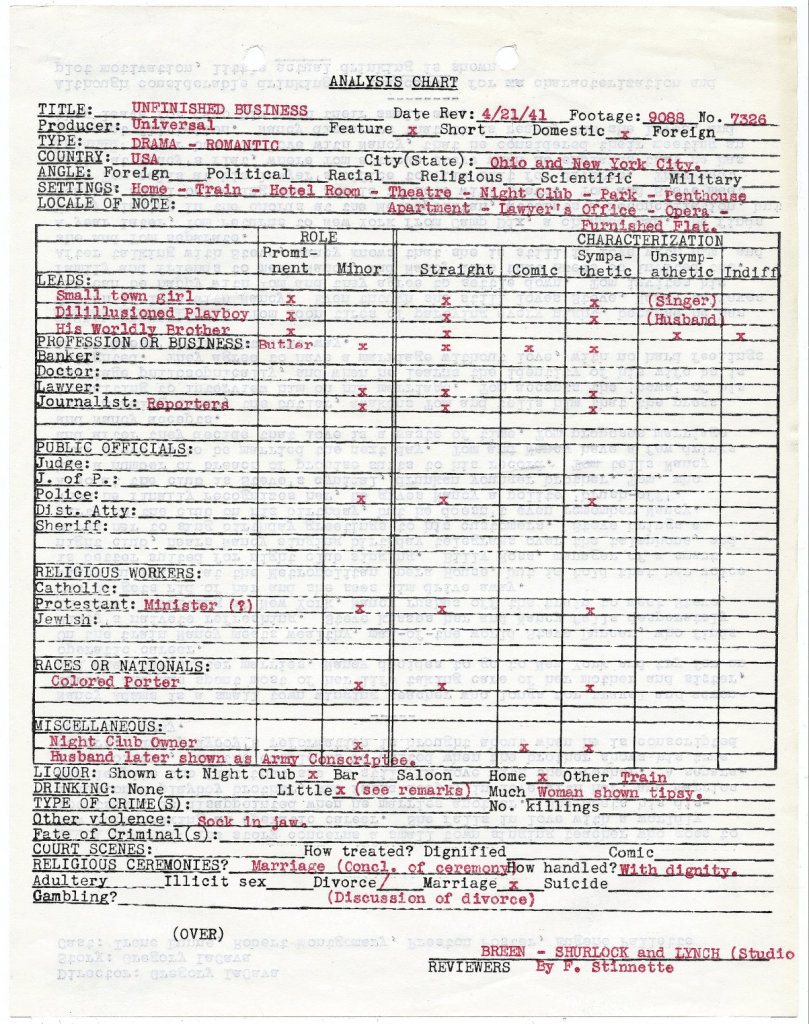

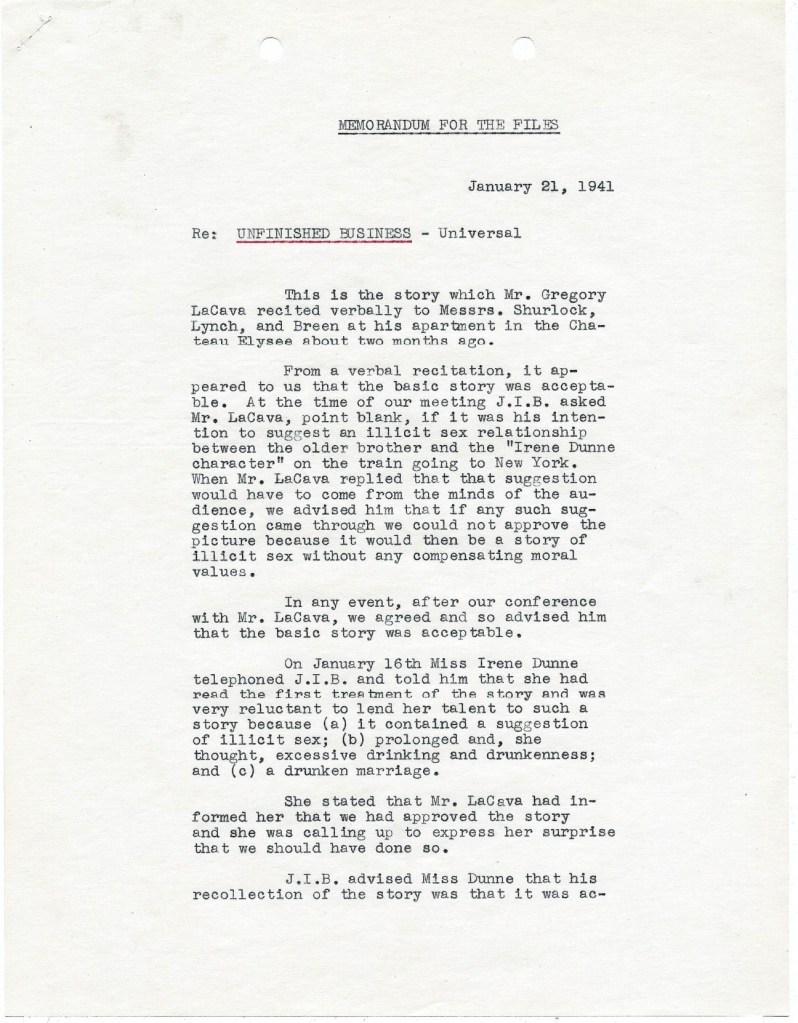

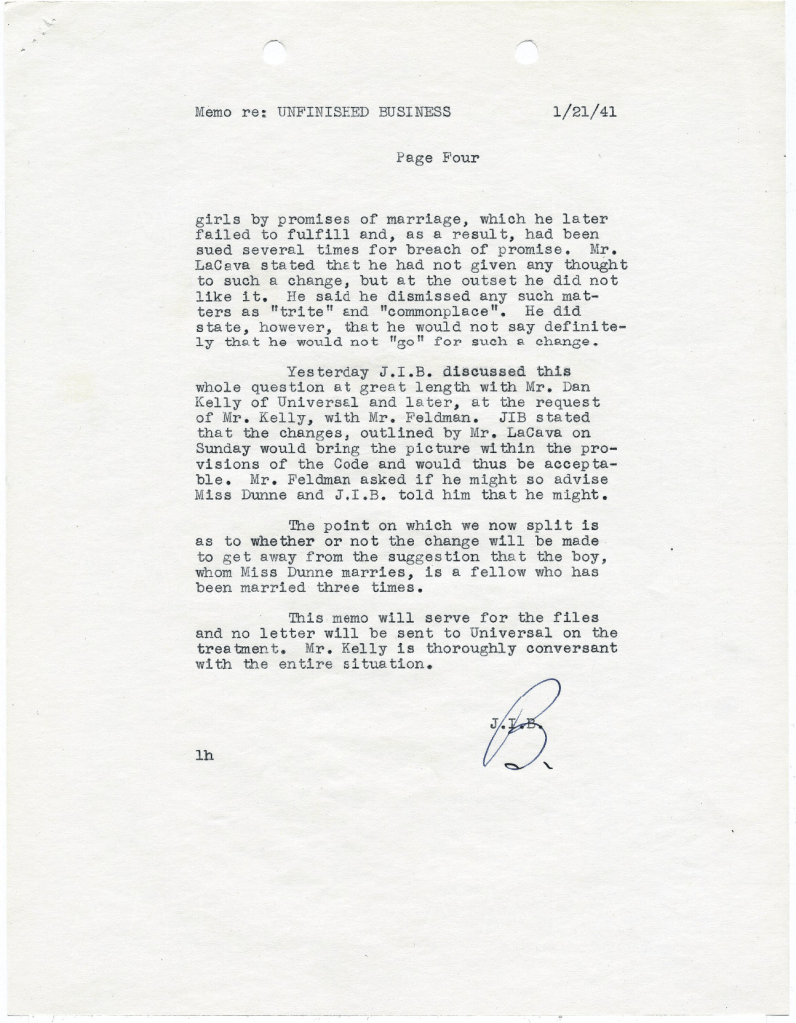

Unfinished Business itself is a more moralistic screwball than other and previous films from La Cava, meaning the rather direct and honest presentation of alcoholism as well as sexuality in the picture was of concern at the time of production due to the Production Code. I’d like to share with you an amusing anecdote regarding how one of these potentially Production Code violating details, the implication that Irene Dunne and Preston Foster had a sexual encounter on the train, remained in the picture. In a memorandum by Joseph Breen on his meeting with La Cava upon request by Dan Kelly of Universal because of his concerns about the inclusion of alcohol and sex in the film, Breen wrote that he discussed the story at length at La Cava’s home, where Breen believed that La Cava did actually agree that any indication that the older brother had had an affair with the girl who later marries his younger brother was not only highly distasteful, but also, in La Cava’s words, “suggestive of incest”. La Cava’s successful navigation of the Production Code to keep this scene in the picture is fascinating when you see the suggestive camera movements following Dunne and Foster’s kiss, and indicative of La Cava’s dedication to his story. The below attachments are the memo and analysis for the Production Code issues. Courtesy of the Margaret Herrick Library:

The 35mm print shown at the BFI was made in 1975 by the BFI, possible for a planned La Cava retrospective that was mentioned in Kingsley Canham’s La Cava filmography file made for the BFI, and the print has been in the BFI National Archive since then. It truly showcases the fluidity of movement in the picture, with the train scene and a later pan-shot to Nancy at the party at her and Duncan’s house being particularly remarkable. La Cava worked with cinematographer Joseph Valentine on the picture, but I wouldn’t be surprised if his impression was the same as She Married Her Boss (1935) and Private Worlds (1935)’s cinematographer’s, Leon Shamroy, who said that ‘You will notice in a La Cava film that there are more master shots than closeups. Instead of simply doing a scene with a series of closeups and getting the individual reaction of each character, La Cava aims to reveal the reaction of each character in the scene to all the others.” I would say La Cava had a just as marvellous visual touch, a playful shove as I like to describe it, as written.

Sources: