The status of La Cava as one of the great forgotten artists of the Golden Age of Hollywood does, unfortunately, lend itself to being forgotten by his peers in memoirs and interview accounts, so when La Cava is remembered and discussed in detail it is always a wonderful surprise. I recently managed to get a hold of a copy of Morrie Ryskind’s memoir, “I Shot an Elephant in My Pyjamas: The Morrie Ryskind Story”, and the detailed account Ryskind provides of his period working with Gregory La Cava on My Man Godfrey (1936) and Stage Door (1937) gives great insight to La Cava’s working style and what made him a unique filmmaker.

I have transcribed Ryskind’s chapter on La Cava below, but just wanted to make note of the obvious point that this is, of course, just one account and can’t be taken as straight fact. Ryskind’s conservatism does taint his narrative of his early years, but his chapter on La Cava is surprisingly, and thankfully, rather honest in La Cava’s increasing reliance on alcohol affecting his work and his relationship with the studios, rather than just his unorthodox filming style.

“As interesting and rewarding as the rewriting assignments were, a career is based on acknowledged credits, and of all the films that bore my name, the greatest satisfaction came from the two that I made with Gregory La Cava: My Man Godfrey and Stage Door.

A few years ago, I happened to receive an inquiry from an overly earnest (is there any other kind?) young film scholar asking me to assist him with some insight into the allegorical implications of My Man Godfrey. As best that I could understand his request, the young man was constructing his thesis around the fact that the title character of Godfrey Parke, the millionaire turned depression bum who takes a job as a butler to a wealthy family on Fifth Avenue and then uses his acumen to save the family from financial ruin, was supposed to be a representation of God. The key to understanding this assertion could be found in Godfrey’s name. Godfrey had brought love to the wealthy family, hence the name GOD-Free, and wasn’t it artistic of me to have devised such a meaningful idea? Well, as all of this came as news to me, the most that I could do for the young man was write back to him and inquire if he were certain that we were discussing the same movie.

The desire to read some sort of symbolic message into the films of the thirties, when our only intent was to entertain, strikes me as a very strange endeavor. Over the years I’ve received a number of similar requests, most of which revolve around whether or not the Marx brothers were meant to be representatives of the world’s nameless masses striking a blow of freedom against the unfeeling upper crust of society. To this, I always respond with a smile and an unequivocal “no.” The Marx Brothers were simply vaudeville performers who switched from singing to comedy when they realized that a laughing audience could be a great deal more beneficial to them than a booing audience when it came time to square up with their creditors. The act worked, and they very wisely stayed with it for the rest of their careers.

As for My Man Godfrey, this wistful little tale from Eric Hatch’s novel, 1011 Fifth Avenue, was based partly on fact. There were numerous incidents of the Wall Street crash of 29 turning millionaires into clerks, laborers, and even butlers, when they could find a position. (What was left of New York’s monied set seemed to prefer the cachet that came from having former Russian aristocrats who had fled the Bolshevik revolution butle for them.) As for the movie’s title, it was originally to have been the same as the novel. The change was made from 1011 Fifth Avenue to My Man Godfrey in deference to the leading man requisites of Mr. William Powell, whose services we had the very unexpected pleasure of obtaining.

Universal Pictures had obtained the screen rights to 1011 Fifth Avenue with the express hope of signing Constance Bennett to play the role of the addle-brained heiress Irene Bullock. Universal was then teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and in dire need of the kind of box office hit that Constance Bennett’s presence would in-sure. Miss Bennett was indeed one of the industry’s biggest money makers at the time, and no one was more aware of the fact or of the prerogatives that come with it than she, as Greg La Cava was soon to discover.

Because of his bifurcated reputation of being a brilliant director and a constant torment to whoever was brave enough to hire him, Greg La Cava bounced back and forth between Hollywood’s studios like a pinball.

One of his assignments landed him at 20th Century-Fox where he was able to channel Constance Bennett’s tempestuous energies into a superior performance in The Affairs of Cellini. On the basis of that accomplishment, and I’m afraid for that reason alone, Greg was asked to direct 1011 Fifth Avenue.

Greg was anxious to accept the Universal’s offer, but the battle scars from The Affairs of Cellini had left him little desire for an encore encounter with Miss Bennett, In her stead, Greg hoped to use Claudette Colbert, whom he had just had such a great success directing in She Married Her Boss for Columbia (whose gates closed behind him with a pronounced finality). To secure Miss Colbert’s participation, Greg utilized the Machiavellian-like ploy of agreeing to direct Miss Bennett, but only on the condition that William Powell be brought in as the co-star. The reasoning behind this was that by making a demand which he knew would be an impossibility to meet, Universal would then owe him a concession-exit Miss Bennett, enter Miss Colbert.

At that time it did seem impossible that William Powell, whose stature at MGM was second only to Clark Gable’s, would agree to loan out at Universal, which had supplanted Columbia at the southern end of the pecking order of the major studios, whose financial collapse was being forecast on a daily basis. But to everyone’s amaze-ment, and no one more so than La Cava, Powell agreed to play Godfrey, conditional on Carole Lombard being brought in from Paramount to be “his” co-star. The executives at Universal had no difficulty in recognizing the advantages of acquiring a star of Miss Bennett’s magnitude without acquiring Miss Bennett’s penchant for provoking tensions and were only too happy to accommodate Mr. Powell’s proviso. It naturally followed that as William Powell was deemed a bigger star than Carole Lombard, then the emphasis of the story-which had the part of the butler being secondary to that of the heiress-would now have to be reversed. This is what led to our new title, and if anyone can draw any allegorical implications from that, I urge them not to miss Harpo’s representation of the Anti-christ in Animal Crackers.

Off-camera, William Powell and Carole Lombard were exactly as they appeared on screen, which made working with them the sort of hoot that makes usage of “working” seem a falsehood. He with his fair for wry understatement and she with her blonde brassiness went at each other for the course of the entire production, but it was obvious for all to see that their insults were only a coverup for a deeply felt affection. I suppose that along with everyone else, I often found myself wondering how it was they could go through a divorce and remain such good friends. The most that Carole would ever volunteer about the subject was a shrug and “It’s better this way.” William Powell was even more reserved about the matter, but once he did tell me that his sole purpose for taking the part was to insure that Carole obtained the role that he felt (correctly) would solidly establish her as a major star.

While there is no disputing the enormous box office appeal that was generated by the combined Powell/ Lombard stardom, I do not wish to overlook the contributions of the Pirandellian perfection of our supporting cast, I still feel it necessary to attribute the ultimate success of My Man Godfrey to Greg La Cava. That being stated, I also feel it necessary to make a qualification. I dislike delving into the private lives of those who are no longer here to speak for themselves, but it would be impossible to discuss Greg’s work without mentioning the effect, both good and bad, that was the result of his drinking problem. He was an alcoholic. Having made this moral trespass, I can at least take some comfort in the fact that it reads somewhat softer than Pandro Berman’s (RKO’s production chief) appraisal, “He’s a drunken bum,” which was pretty much the sentiment of every studio head that Greg worked for. Be that as it may, Gregory La Cava, with his remarkable sense of comic timing and his refined flair for improvisation, still remains in my opinion as the finest comedy director that I ever worked with.

As a partnership, Greg and I hit off from the word go. There were a number of reasons for this, the most welcome among them being that the disdain that Greg held for most conventions also extended to his regard for the

standard screenplay format. If you’ve ever seen a screenplay from that era, with their stultifying preponderance of scene numbers, CAPITAL LETTERS, and camera di-rections, you would have no trouble in understanding why this was such a blessing:

237 INT. OPERA HOUSE-NIGHT-ESTABLISHING SHOT From

Groucho’s P.o.V., CAMERA trucks into med. two shot of Harpo and

Chico-followed by 180 degree CAMERA LEFT PAN to pick up entrance of Mrs. Claypool.

Even though this tended to make scripts read like engineering manuals, the prevailing wisdom of the industry had declared the form inviolable and this is what proved to be the undoing of so many writers. If I thought of it in terms of mechanics, I too was stopped, but by approaching it from the perspective of a student applying an algebraic theorem, I could manage to get by. When we worked on A Night at the Opera, I tried to help George Kaufman with this method, but he refused to even consider dealing with “that dam camera gibberish.” One of the few conversations that I had with F. Scott Fitzgerald was taken up with this same subject. In Fitzgerald’s case, it was doubly sad, as he had made a very determined effort to come to grips with this alien craft, but after four years of trying he was to have but a single screen credit.

As Greg didn’t require camera directions to be written down, “I wouldn’t use them anyway,” all I had to do was tell the story as simply and clearly as I could. Had I not been able to take this shortcut, I seriously doubt that Godfrey would have been made.

There has long been an argument in Hollywood over the consequences of allowing novelists and playwrights to adapt their own works to the screen. I’m afraid that Mr. Hatch, who had made the movie rights to his story provisional on his being allowed to write the first draft of the screenplay, set a bad example for anyone who might wish to take up the cause on behalf of all the authors who have decried the fate of their creations in the hands of us “Hollywood hacks.” Mr. Hatch did write a very good novel, whatever happened to him afterward I couldn’t say, but when I was shown his completed draft, it became very obvious very quickly that his instincts were literary not cinematic. With the exception of the page numbers, nothing from the original had been omitted. All of the prose had been converted into dialogue, which, coupled with dialogue that already existed, resulted in a script that, had it been filmed as written, would have played like one of those marathons that Eric Von Stroheim used to make.

Considering that it was less than a month before the production was supposed to begin, Greg didn’t seem terribly bothered about this. After handing me a copy of the original book, he merely smiled and said, “We’re all expecting something very nice from you.” I appreciated this confidence, but I can’t say I was overly pleased about the time squeeze that I had to contend with in order to justify it. When the actual filming began I only had the first half done, and for the next few weeks after that, it took every ounce of concentration that I could muster to stay ahead of the production as it kept closing in on me. About midway into the filming I did get caught up short, but it was from circumstances over which I had no control.

Greg was a member of a notorious drinking cabal that included John Barrymore and W. C. Fields, both of whom arrived on the set one Saturday afternoon to wait for Greg. Barrymore seemed much more subdued than his reputation would suggest but Fields was a ripsnorting replica of his screen persona. When we were introduced, he greeted me with, “Ah, yes, the little Hebrew scribe, and then proceeded to make an examination of his fingers to make sure that he hadn’t lost any in the hand-shakes. When we knocked off that afternoon, the three of them set off on a bender which landed Greg in the hospital the next day.

On Monday morning, our executive producer Charles Rogers was bursting with livid retrospections about hav. ing hired Greg. After announcing that he had been fired, he asked (ordered) me to take over as director. The production was on a very tight schedule due to William Powell’s commitment to begin filming a sequel to The Thin Man just three weeks after the projected date of Godfrey’s wrap-up. There couldn’t be any delay, and as I was the one closest to the story, the production was now in my hands. Whether I was closest to the story or not, the transition from the writer’s cubicle to the director’s chair was one that I wasn’t prepared to make. I might have been able to direct a stage play where I would only have to contend with actors, but all of this business with the lights and camera lens was completely beyond the province of my ability.

In an effort to forestall what surely would have been a fiasco, I suggested (pleaded) that we wait at least a week before taking any action. Greg had always been able to rebound from his spells before, and I still had several days work yet to do on the script. Although William Powell could see the wisdom of my not attempting a directorial debut with an unfinished script, the delay would eat into his vacation time, and that prospect moved him to a fit of grousing that was very uncharacteristic of him. After an impassioned entreaty by Charles Rogers, he reluctantly agreed, but I believe that if the truth were known, for Carole Lombard’s sake he would have worked right up until the day he was to report back to MGM.

Rogers made an announcement to the press that the production would be shut down for a week while Greg recuperated from the flu. I seriously doubt that this fooled anyone, but it did give me the opportunity to engage myself in a few all-night sessions which saw the script through to its completion. On Friday of that week, the fervent praying that I had suddenly become reacquainted with was answered; Greg would be discharged from the hospital the following day and would return to work on Monday. On Sunday, Greg came to my house for a “script consultation.” This was nothing more than a meaningless gesture to appease the Universal hierarchy, but as long as it contributed to my being taken off the hook, I was more than willing to go through the motions.

Outwardly, Greg didn’t appear to be any worse for the wear, but as we talked, a noticeable edginess began to overtake him. About fifteen minutes into our talk, he suddenly slammed his hand on the table, “What’s a man have to do to get offered a drink in this place?” I supposed that I could have rooted around in one of the pantry shelves and come up with a bottle of something, but it hardly seemed like a sound idea to be offering a drink to a man who had just spent a week shaking off the heebie jeebies. When I apologized with, “Sorry, Greg, there’s not a drop in the house,” he exploded. “What are you, a Jewish Mormon?” I tried to smile this off and bring his thoughts back to the script, but he wouldn’t be pla-cated. “I passed a couple of stores coming over here,” he said with a glint of Dickensian glee lighting up his face, “we can send out for something.” I reminded him about the Sunday liquor laws, but the concept was apparently too foreign for him to grasp. At that point there didn’t seem to be anything left to be gained by tactfulness, so I just told him straight out that with all the jobs that were at stake, I wasn’t about to be party to his going back in the padded room with the imaginary spiders crawling on the walls. I was just starting to get wound up in my spiel when he cut my pontifications short with, “All right. All right, give me a damn coke,” which I did, and which he accepted with the distaste of a man being offered radioactive waste.

I wish that I could report that my little lecture had some sort of positive effect on Greg’s problem, but the next morning on the set, the coffee cup (a ruse that he was employing long before anyone had ever heard of Jackie Gleason) was on the stand beside his chair. Thankfully, his drinking pals maintained a judicious distance and Greg was able to keep himself in balance until he finished directing the film that would become the biggest box office hit that Universal had scored until that time.

A runaway hit of My Man Godrey’s nature has a way of invoking a lot of forgiveness. Universal responded in kind by making Greg some very generous offers. Greg responded in character by going on a celebratory binge that landed him back in the padded room, and Universal quietly decided that they could get along without Mr. La Cava. After re-emerging from his post-Godfrey situation, Greg signed on with RKO, and after a few of my own misadventures at Universal (more than this anon), I caught up with him about six months later.

RKO was the smallest of the seven major studios, which helped-especially during Pan Berman’s steward-ship-to give it a family-like atmosphere. For that reason I was always happy-at least until Pan Berman left-to land an assignment there. Although the studio itself consisted of only a few sound stages on a lot adjacent to the sprawling Paramount complex, its output in terms of quality more than made up for its lack of quantity: Little Women, Morning Glory, King Kong, Bringing Up Baby, Bachelor Mother, Gunga Din, Kitty Foyle, Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, and Suspicion, to name a few. But with all due respect to the impressive roster of classics, I felt that RKO’s greatest distinction came from its impressive series of musicals with Fred Astaire and the ever so delectable Ginger Rogers.

I really wanted to work on one of the A/R’s (and who wouldn’t?), which sort of became a reality as my first project at RKO. They gave me a story with a New York setting to adapt, but my involvement ended after only two very enjoyable weeks of working on the script. Just when I got to the scene where I had Fred and Ginger dancing on top of the Empire State Building, La Cava learned that we were both working for the same studio. He asked Pandro Berman to have me reassigned to his project, and before I knew what hit me, I was back in the midst of another La Cava mixmaster.

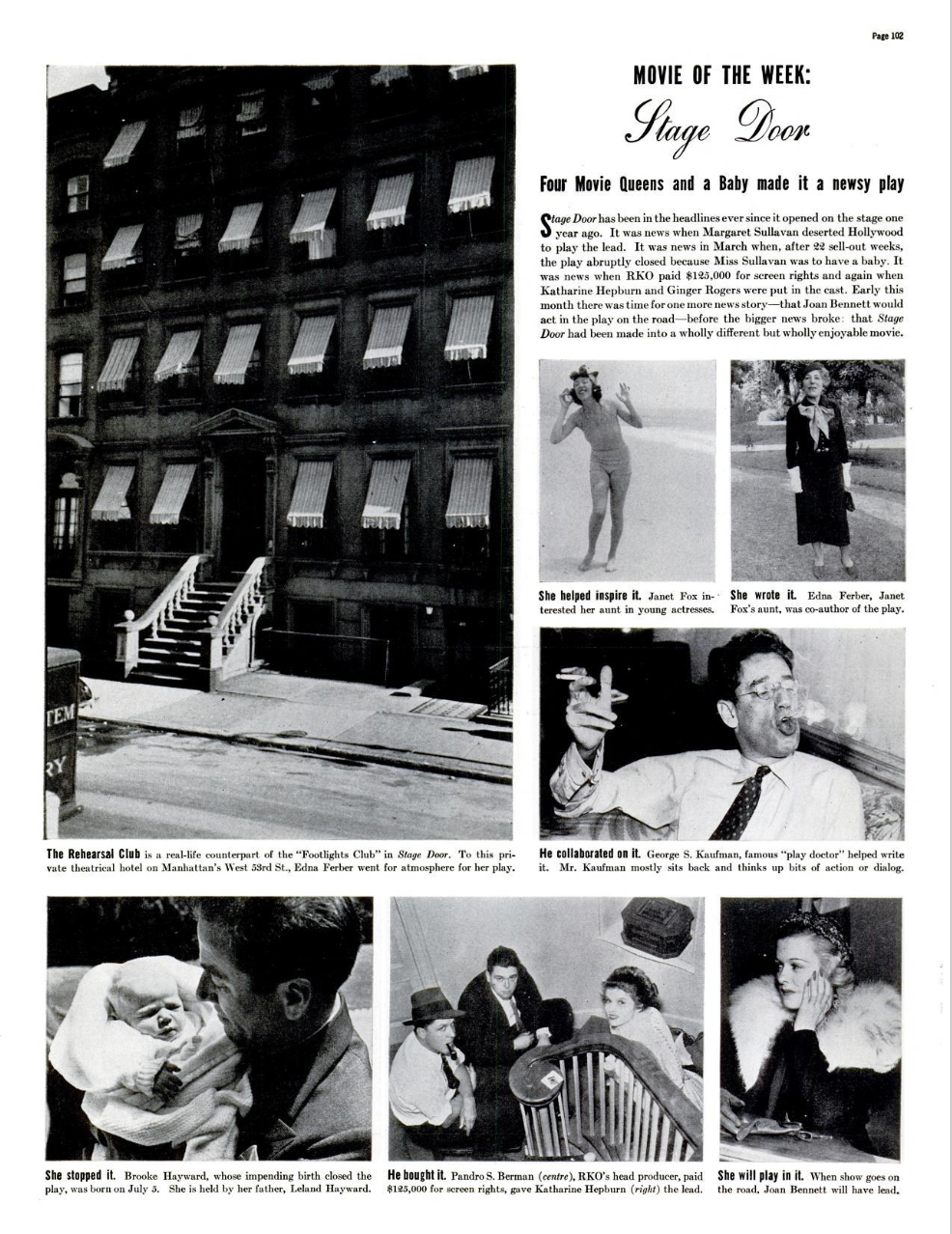

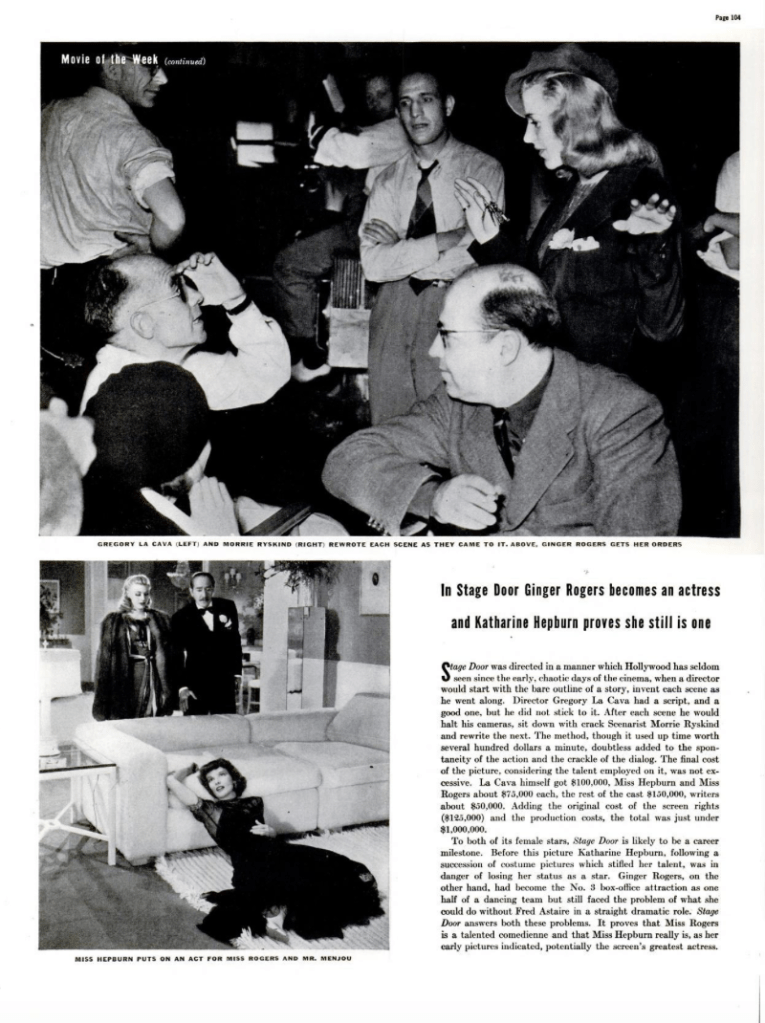

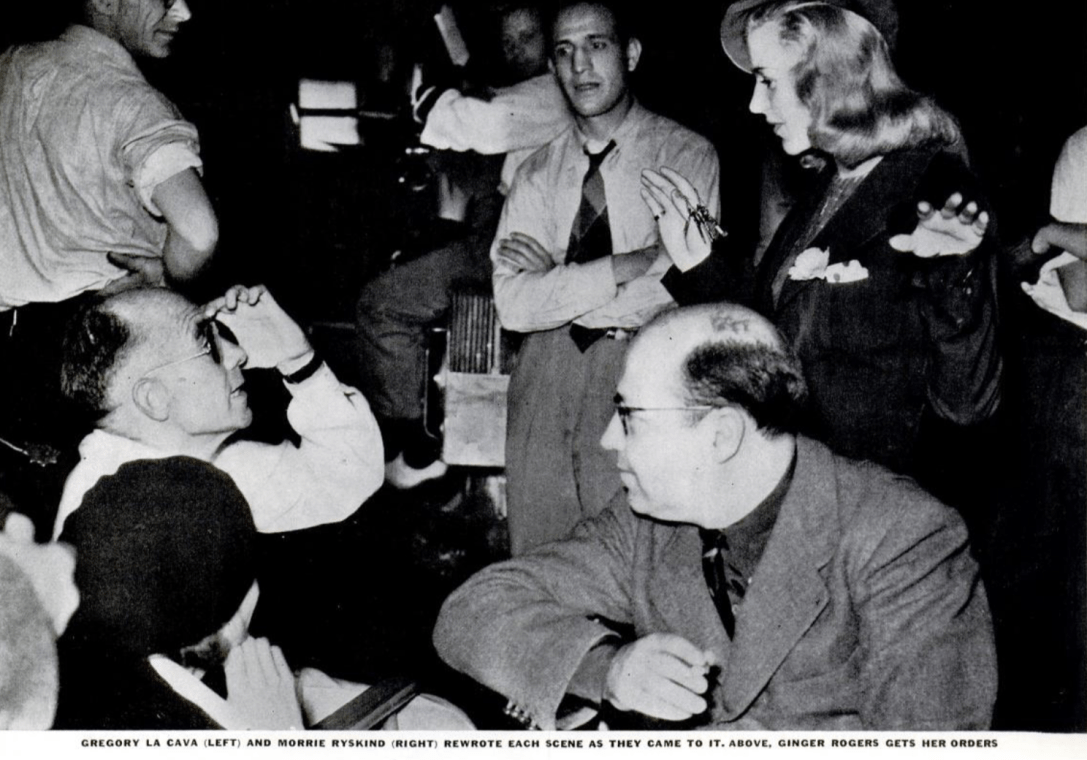

Despite all the pressures that were automatically associated with Greg’s scattershot approach to film making-and this one got so topsy turvy that Life magazine came in to do a spread on us—I was glad, in the end, to have been a part of Stage Door, in that it gave me a chance to say everything I had ever wanted to say about Broadway: the good, the bad, the ugly, and the beautiful. It also gave Patrick, Constance Collier, Eve Arden, and Lucille Ball in me a chance to work with Andrea Leeds, Ann Miller, Gail support of Ginger Rogers and Katharine Hepburn, and if there has ever been a greater cast of female talent assembled for one movie, I’ve yet to see it.

Ostensibly, Stage Door was to be based on the play that George Kaufman rushed back to New York to write with Edna Ferber when our collaboration on A Night at the Opera was finished. Tony Veiller, one of the best writers in the business, had made an adaptation, but Greg was unhappy over it being too faithful to the original. I hadn’t seen the play, but when I read the script I could understand why.

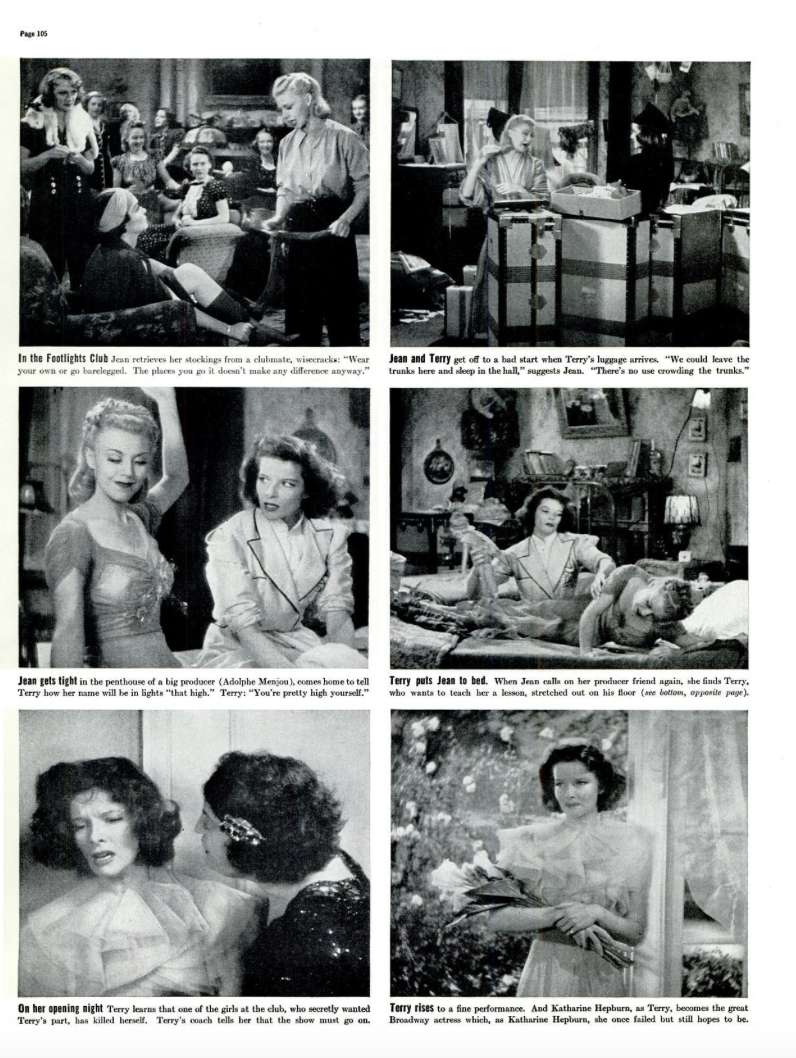

The plot of Stage Door was taken up with struggles of two would-be Broadway actresses sharing a room at a third-rate boarding house. One of them perseveres against all odds and becomes a star, while the other was shown to be selling out her virtue by going to Hollywood. This was one of George’s favorite themes, and as he had already worked it over pretty well with Marc Connelly in Merton of the Movies and with Moss Hart in Once in a Lifetime, I felt that it had lost most of its bite. I loved Broadway, but my experiences there hadn’t convinced me that Hollywood had a monopoly on compromises, con artists, and prima donnas. Greg asked me if I could rewrite the opening scene from that perspective. Since the production was scheduled to begin in less than a week, I figured that this was all that would be asked of me and then I could get back to the Astaire/Rogers project.

What I did like about Stage Door was the girls’ theatrical hotel where most of the story takes place. The Footlights Club, as Kaufman and Ferber had it, was loosely based on the Rehearsal Club which was still in existence on West 58th Street until just a few years ago. During my bachelor days, I had begun many a date in the Rehearsal Club’s lobby, and from the memory of the girls’ wisecracks to each other as they went up and down the main staircase came the scene that I presented to La Cava a few days later. He looked the pages over for a few minutes and then said, “This is great! Now go home and get started on the rest of it, because I’m going to shoot this on Thursday.”

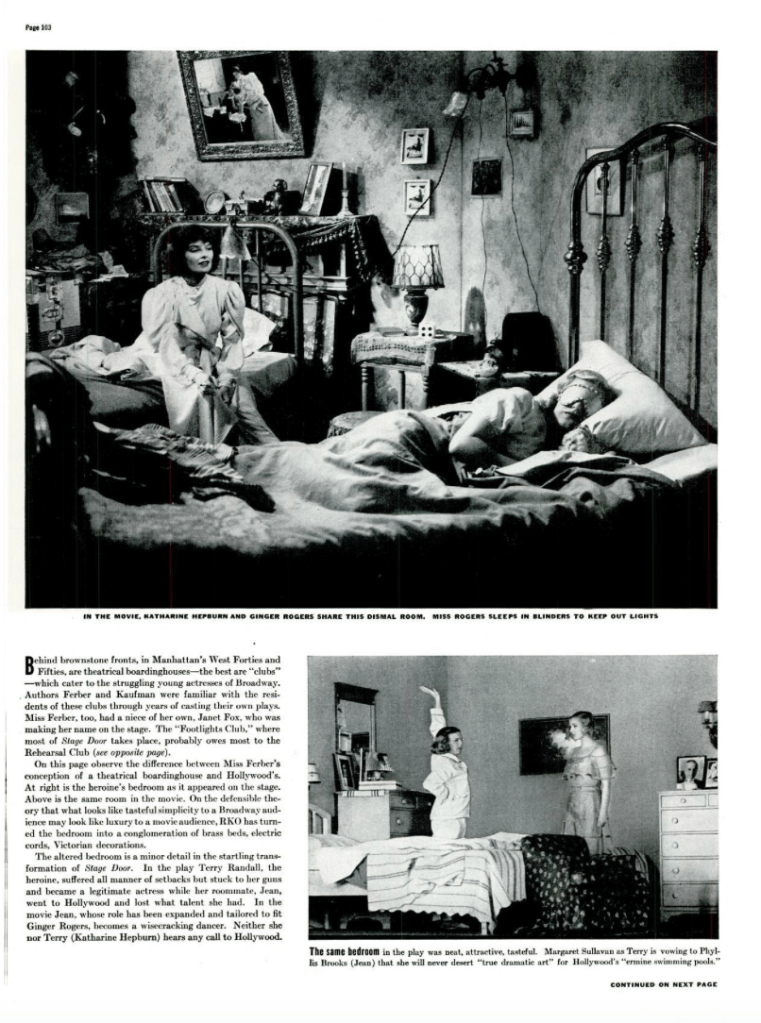

It was to go that way for the entire production, and when we were finished, the only thing that remained from the original Kaufman/Ferber story was the title. In order to come up with a new plot and dialogue, I had to work on the script all day at the studio and most of the night at home. And even with that effort, I was never to be more than a one day ahead of the filming, and there were many times when everybody had to stand around and wait while I sat off to one side of the set feverishly trying to finish the next scene.

None of the cast had ever worked that way before, and it seemed to be especially hard on Katharine Hepburn, who was used to long rehearsal periods. About midway into the shoot she stopped me and asked, “Morrie, how is this going to end? Do I get Dolf or does Ginger?” It was a valid question, but the best answer I could give her at the time was, “Don’t ask me that now, Kate, because I’m just not that far ahead yet.”

There were similar apprehensions emanating from the head office, but when the rushes were screened each day, everyone agreed that although we didn’t know exactly where we were going with this story, we were definitely headed in the right direction. By the way, the Dolf that Miss Hepburn made reference to was, of course, that inimitable cad of all cads, Adolph Menjou, who held up the male end of Stage Door by himself. We became close friends during the filming, and like everyone else that came within the periphery of that modern Beau Brummel’s sartorial splendor, to know him was to suffer in comparison. Whenever he could visit our house, my wife would make a great production of taking careful notes on what he was wearing. She would then coax me into buying the same stylish materials, arrange some occasion to wear them, and just before we went out, would look me over and shake her head disconsolately. (I couldn’t understand it either; I think she takes notes badly.) And while there was no denying the stellar brilliance of the Stage Door cast, the ultimate success of the picture belonged to Greg La Cava. It unfortunately followed that Greg’s success was attributable to his drinking which, sadly, had not changed since we made My Man Godfrey. Once again, this led to some painfully embarrassing moments, but from that same Muse who often caused him to fumble for names and stumble into furniture, came moments of sheer comedic genius, hundreds of them, all of which were conceived on the spot, and as a result of that improvisational crackle, Stage Door was imbued with a vitality that, in my opinion, hasn’t diminished one iota in the near half-century since it was made.

In hopes that the La Cava-Ryskind winning streak would become three for three, Pan Berman asked us to take on Room Service with the Marx Brothers. It’s pretty interesting to contemplate what might have resulted from a La Cava-Marx Brothers pairing, but it was not to be. Realizing that he had reached a now or never point, Greg dropped out of the project and spent the next two years coming to grips with his drinking problem. I was sorry to miss out on working with him again, especially with the potential that this project offered, but for Greg’s sake I was happy that he was finally making the effort. And as for Room Service, I seriously doubt that even Greg’s formidable talents could have saved it from being a misfire.

Aside from the fact that the original play wasn’t a musical and that it wasn’t written specifically for the Marx Brothers, both of which were dangerous deviations from the formula that had given the boys their past successes, the biggest problem that I had to contend with was the one of the setting. Ninety percent of the story was taken up with Groucho’s stalling tactics to avoid being evicted from his hotel room. A theatrical audience will accept a story that takes place in one setting; in fact, fewer settings usually enhance a play’s charm by shifting the emphasis toward the quality of the dialogue. But with movies tending to be primarily a visual medium, a one-set story can seem claustrophobic before the end of the first reel.

The problem of setting wasn’t lost on the RKO hierarchy, but then again, neither was the fact that they had shelled out $225,000 for the film rights to Room Service. It was the largest single expenditure that the studio had ever made, and with an outlay of that size at stake, they weren’t anxious to tamper with a proven success as we had done with Stage Door. Room Service had been a smash on Broadway; it was to be transferred intact (with a subsequent success) to the screen.

Well, RKO got a success out of Room Service, but unfortunately it wasn’t with our version. There were a lot of funny moments in our effort, but on the whole it was a cramped, badly paced miscalculation that was dismissed by the critics and ignored by the public, which gives me the distinction of having written the best and the worst of the Marx Brothers movies. (I am, if nothing else, at least versatile.) During the war, RKO turned Room Service into the musical Step Lively with Frank Sinatra and George Murphy. The story was expanded beyond the one room, the musical numbers were properly integrated into the continuity, and the result was as entertaining as ours wasn’t. Of course, if one would only take the trouble to look, there are good points to be found in every endeavor, and it didn’t take much looking to determine that Lucille Ball was the best thing about Room Service. This was Miss Ball’s first starring role, and I do take some pride in knowing that I was able to help make that possible.

When we were making Stage Door, Miss Ball was a $50 a week contract player for RKO. She was assigned to the picture, but in the original version her part wasn’t much more than a walk-on. While we were making the film, all the girls would gather their chairs into a circle for a gabfest between scenes. My chair was close to their baili-wick, and a lot of anecdotes that emanated from their sessions ended up in the script. But what really impressed me was Miss Ball’s voice. There was just something very pleasant about the way it fell on my ears, and on the basis of that attraction I went to great lengths to build up her part. Greg agreed with my intentions, and he also went to some lengths to showcase Miss Ball’s ability. When Greg was casting Room Service, he gave Miss Ball the lead, and the RKO chieftains stayed with his choice after Greg left the project. It was a wise decision, but it was followed by a boner. With her star on the rise, Miss Ball deservedly asked for a higher salary and was promptly dropped by the studio. I guess you could say that she exacted a somewhat classic revenge. After striking the “I Love Lucy” motherlode, Miss Ball bought RKO.”

Notes:

- The LIFE magazine spread that Ryskind mentions in this can be read below: