The “La Cava Method” of improvisation and the alteration of dialogue to fit the actor’s real personality became of particular interest following My Man Godfrey (1936), but there seemed to be a definite change in interested in the director’s particular idiosyncrasies following the release of Stage Door (1937). It is possibly due to the popularity of the stage play and the complete difference and direction the film takes that interest turned to the man behind this microcosm of Hollywood and its personalities that his adaptation creates. I mention this because I was fortunate to find an old Collier’s magazine featuring an interview and introduction to Gregory La Cava, and wonderfully surprised to see a biographical account that lines up with La Cava’s previous statements, and previous directorial introductions, about his life before motion pictures. Of course, as always, with magazine interviews and biographical narratives there is a bending of the truth. It’s also rather amusing to see that writer Quentin Reynolds held the impression that La Cava’s did not hold a particularly strong interest in film, when accounts back from his animation days recall his obsessive interest in replicating as close to humanity with watching Charlie Chaplin’s work. Reynolds does conclude his discussion with La Cava on an interesting note with asking directly about La Cava’s technique, his “Lubitsch Touch”, to which La Cava wonderfully replies: “I have no technique. I have no formula. Give me a story about human behavior and I’ll put it on the screen. I won’t make a phony story.” La Cava’s fascination with the human condition melded perfectly with the times of the Depression, as most of his great films circulated and confronted, and La Cava’s confession to no technique shows the immediate moment and human response as exactly his technique.

I have transcribed the piece below and I have attached a scan of my copy at the end of this post:

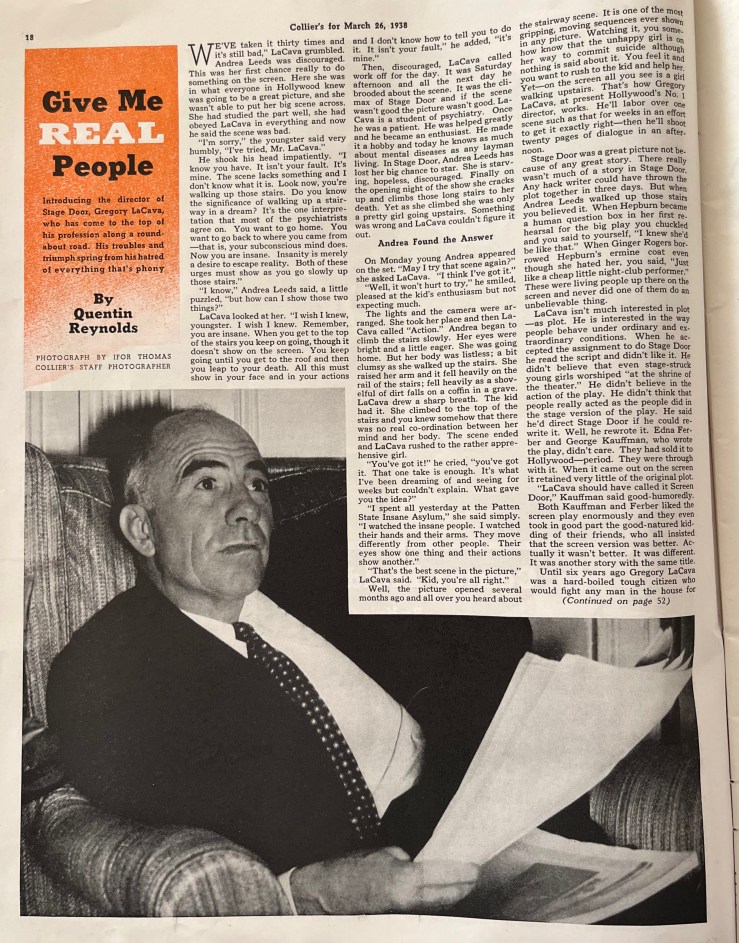

“We’ve taken it thirty times and it’s still bad,” LaCava grumbled.

Andrea Leeds was discouraged.

This was her first chance really to do something on the screen. Here she was in what everyone in Hollywood knew was going to be a great picture, and she wasn’t able to put her big scene across.

She had studied the part well, she had obeyed LaCava in everything and now he said the scene was bad.

“I’m sorry,” the youngster said very humbly, “I’ve tried, Mr. LaCava.” He shook his head impatiently. “I know you have. It isn’t your fault. It’s mine. The scene lacks something and I don’t know what it is. Look now, you’re walking up those stairs. Do you know the significance of walking up a stairway in a dream? It’s the one interpretation that most of the psychiatrists agree on. You want to go home. You want to go back to where you came from—that is, your subconscious mind does. Now you are insane. Insanity is merely a desire to escape reality. Both of these urges must show as you go slowly up those stairs.”

“I know,” Andrea Leeds said, a little puzzled, “but how can I show those two things?”

LaCava looked at her. “I wish I knew, youngster. I wish I knew. Remember, you are insane. When you get to the top of the stairs you keep on going, though it doesn’t show on the screen. You keep going until you get to the roof and then you leap to your death. All this must show in your face and in your actions and I don’t know how to tell you to do it. It isn’t your fault,” he added, “it’s mine.”

Then, discouraged, LaCava called work off for the day. It was Saturday afternoon and all the next day he brooded about the scene. It was the climax of Stage Door and if the scene wasn’t good the picture wasn’t good. LaCava is a student of psychiatry. Once he was a patient. He was helped greatly and he became an enthusiast. He made it a hobby and today he knows as much about mental diseases as any layman living. In Stage Door, Andrea Leeds has lost her big chance to star. She is starving, hopeless, discouraged. Finally on the opening night of the show she cracks up and climbs those long stairs to her death. Yet as she climbed she was only a pretty girl going upstairs. Something was wrong and LaCava couldn’t figure it out.

Andrea Found the Answer

On Monday young Andrea appeared on the set. “May I try that scene again?” she asked LaCava. “I think I’ve got it.”

“Well, it won’t hurt to try,” he smiled, pleased at the kid’s enthusiasm but not expecting much.

The lights and the camera were arranged. She took her place and then LaCava called “Action.” Andrea began to climb the stairs slowly. Her eyes were bright and a little eager. She was going home. But her body was listless; a bit clumsy as she walked up the stairs. She raised her arm and it fell heavily on the rail of the stairs; fell heavily as a shovelful of dirt falls on a coffin in a grave.

LaCava drew a sharp breath. The kid had it. She climbed to the top of the stairs and you knew somehow that there was no real coordination between her mind and her body. The scene ended and LaCava rushed to the rather apprehensive girl.

“You’ve got it!” he cried, “you’ve got it. That one take is enough. It’s what I’ve been dreaming of and seeing for weeks but couldn’t explain. What gave you the idea?”

“I spent all yesterday at the Patten State Insane Asylum,” she said simply. “I watched the insane people. I watched their hands and their arms. They move differently from other people. Their eyes show one thing and their actions show another.”

“That’s the best scene in the picture,” LaCava said. “Kid, you’re all right.”

Well, the picture opened several months ago and all over you heard about the stairway scene. It is one of the most gripping, moving sequences ever shown in any picture. Watching it, you somehow know that the unhappy girl is on her way to commit suicide although nothing is said about it. You feel it and You want to rush to the kid and help her.

Yet-on the screen all you see is a girl walking upstairs. That’s how Gregory LaCava, at present Hollywood’s No. 1 director, works. He’ll labor over one scene such as that for weeks in an effort to get it exactly right-then he’ll shoot twenty pages of dialogue in an afternoon.

Stage Door was a great picture not because of any great story. There really wasn’t much of a story in Stage Door. Any hack writer could have thrown the plot together in three days. But when Andrea Leeds walked up those stairs you believed it. When Hepburn became a human question box in her first rehearsal for the big play you chuckled and you said to yourself, “I knew she’d be like that.” When Ginger Rogers borrowed Hepburn’s ermine coat even though she hated her, you said, “Just like a cheap little night-club performer.” These were living people up there on the screen and never did one of them do an unbelievable thing.

LaCava isn’t much interested in plot—as plot. He is interested in the way people behave under ordinary and extraordinary conditions. When he accepted the assignment to do Stage Door he read the script and didn’t like it. He didn’t believe that even stage-struck young girls worshiped “at the shrine of the theater.” He didn’t believe in the action of the play. He didn’t think that people really acted as the people did in the stage version of the play. He said he’d direct Stage Door if he could rewrite it. Well, he rewrote it. Edna Ferber and George Kauffman, who wrote the play, didn’t care. They had sold it to Hollywood-period. They were through with it. When it came out on the screen it retained very little of the original plot.

“La Cava should have called it Screen Door,” Kauffman said good-humoredly.

Both Kauffman and Ferber liked the screen play enormously and they even took in good part the good-natured kidding of their friends, who all insisted that the screen version was better. Actually it wasn’t better. It was different. It was another story with the same title.

Until six years ago Gregory LaCava was a hard-boiled tough citizen who would fight any man in the house for two dollars (and probably lose) and who never said “No” when drinking unless someone asked, “Have you had enough?” He had more enemies than a centipede has legs. He had led a lusty, vigorous life. He had never bothered much about thinking—he felt. If he wanted to do something he did it no matter what the consequences. One day he woke up, shook his head in bewilderment and said to himself, “There’s something wrong with me. I’d better find out what it is because I’m going nowhere fast.”

No one in Hollywood would give him a job. He says he was a washed-up bum.

He was thirty-six and he was all done—as well done as a twenty-minute hamburger. Everywhere he looked there was trouble. Even the Hollywood bartenders gave him only prop smiles.

Someone persuaded him to go to a psychiatrist.

“Sure,” he said sarcastically, “I’ll go. That’s a guy who reads leaves in teacups, isn’t it? Or finds water with a crooked stick or does voodoo? Sure, I’ll go.”

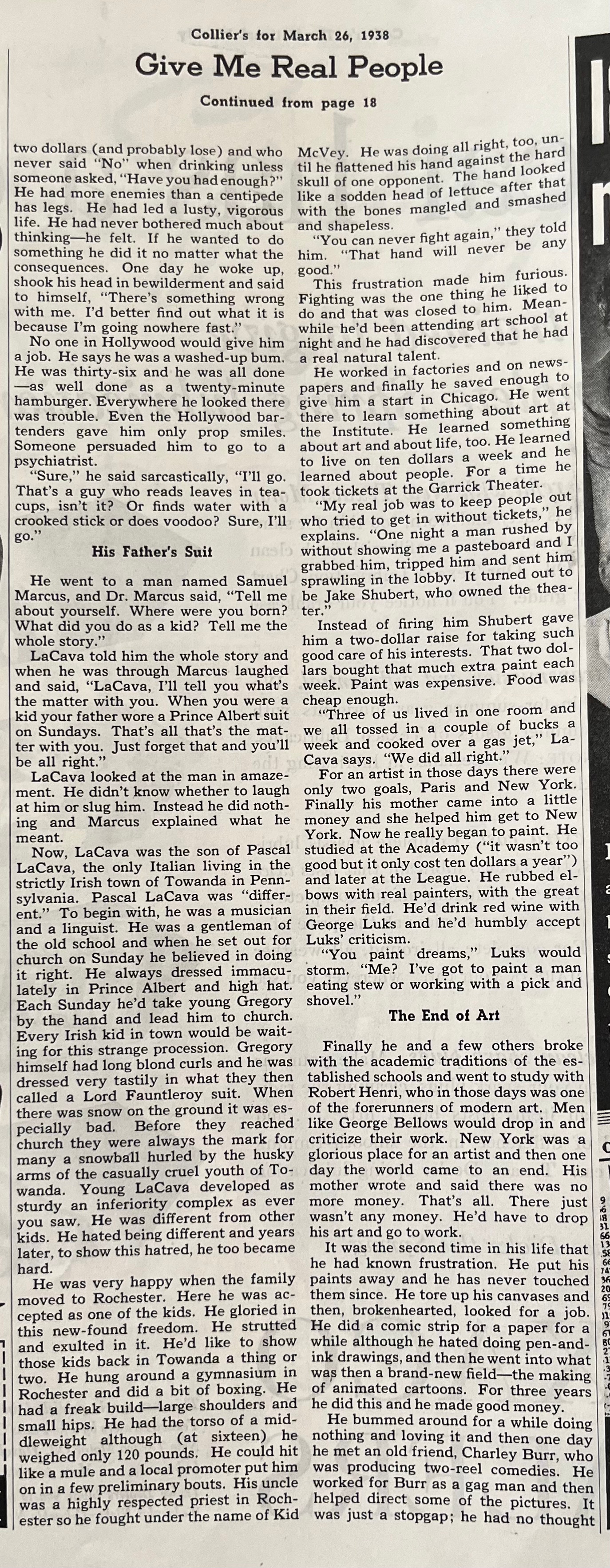

His Father’s Suit

He went to a man named Samuel Marcus, and Dr. Marcus said, “Tell me about yourself. Where were you born? What did you do as a kid? Tell me the whole story.”

LaCava told him the whole story and when he was through Marcus laughed and said, “LaCava, I’ll tell you what’s the matter with you. When you were a kid your father wore a Prince Albert suit on Sundays. That’s all that’s the matter with you, Just forget that and you’ll be all right.

LaCava looked at the man in amazement. He didn’t know whether to laugh at him or slug him. Instead he did nothing and Marcus explained what he meant.

Now, LaCava was the son of Pascal LaCava, the only Italian living in the strictly Irish town of Towanda in Pennsylvania. Pascal LaCava was “different.” To begin with, he was a musician and a linguist. He was a gentleman of the old school and when he set out for church on Sunday he believed in doing it right. He always dressed immaculately in Prince Albert and high hat. Each Sunday he’d take young Gregory by the hand and lead him to church.

Every Irish kid in town would be waiting for this strange procession. Gregory himself had long blond curls and he was dressed very tastily in what they then called a Lord Fauntleroy suit. When there was snow on the ground it was especially bad. Before they reached church they were always the mark for many a snowball hurled by the husky arms of the casually cruel youth of Towanda. Young LaCava developed as sturdy an inferiority complex as ever you saw. He was different from other kids. He hated being different and years later, to show this hatred, he too became hard.

He was very happy when the family moved to Rochester. Here he was accepted as one of the kids. He gloried in this newfound freedom. He strutted and exulted in it. He’d like to show those kids back in Towanda a thing or two. He hung around a gymnasium in Rochester and did a bit of boxing. He had a freak build-large shoulders and small hips. He had the torso of a middleweight although (at sixteen) he weighed only 120 pounds. He could hit like a mule and a local promoter put him on in a few preliminary bouts. His uncle was a highly respected priest in Rochester so he fought under the name of Kid McVey. He was doing all right, too, until he flattened his hand against the hard skull of one opponent. The hand looked like a sodden head of lettuce after that with the bones mangled and smashed and shapeless.

“You can never fight again,” they told him. “That hand will never be any good.”

This frustration made him furious. Fighting was the one thing he liked to do and that was closed to him. Meanwhile he’d been attending art school at night and he had discovered that he had a real natural talent.

He worked in factories and on newspapers and finally he saved enough to give him a start in Chicago. He went there to learn something about art at the Institute. He learned something about art and about life, too. He learned to live on ten dollars a week and he learned about people. For a time he took tickets at the Garrick Theater.

“My real job was to keep people out who tried to get in without tickets,” he explains. “One night a man rushed by without showing me a pasteboard and I grabbed him, tripped him and sent him sprawling in the lobby. It turned out to be Jake Shubert, who owned the theatre.”

Instead of firing him Shubert gave him a two-dollar raise for taking such good care of his interests. That two dollars bought that much extra paint each week. Paint was expensive. Food was cheap enough.

“Three of us lived in one room and we all tossed in a couple of bucks a week and cooked over a gas jet,” LaCava says. “We did all right.”

For an artist in those days there were only two goals, Paris and New York. Finally his mother came into a little money and she helped him get to New York. Now he really began to paint. He studied at the Academy (“it wasn’t too good but it only cost ten dollars a year”) and later at the League. He rubbed elbows with real painters, with the great in their field. He’d drink red wine with George Luks and he’d humbly accept Luks’ criticism.

“You paint dreams,” Luks would storm. “Me? I’ve got to paint a man eating stew or working with a pick and shovel.”

The End of Art

Finally he and a few others broke with the academic traditions of the established schools and went to study with Robert Henri, who in those days was one of the forerunners of modern art, Men like George Bellows would drop in and criticize their work. New York was a glorious place for an artist and then one day the world came to an end. His mother wrote and said there was no more money. That’s all. There just wasn’t any money. He’d have to drop his art and go to work

It was the second time in his life that he had known frustration. He put his paints away and he has never touched them since. He tore up his canvases and then, brokenhearted, looked for a job He did a comic strip for a paper for a while although he hated doing pen-and-ink drawings, and then he went into what was then a brand-new field-the making of animated cartoons. For three years he did this and he made good money.

He bummed around for a while doing nothing and loving it and then one day he met an old friend, Charley Burr, who was producing two-reel comedies. He worked for Burr as a gag man and then helped direct some of the pictures. It was just a stopgap; he had no thought of ever seriously entering the field of pictures.

Richard Dix was making pictures at Astoria then for Famous Players. Bill LeBaron was running the show. LaCava finally got a job on the lot doing a little writing, sticking gags in pictures and in general making himself useful.

Then Dix took a liking to this outspoken young Italian and he insisted that LaCava be given a directing assignment.

LeBaron eventually gave LaCava a chance and he made the most of it. He co-directed a number called Lucky Devil, an auto race story. LaCava had to take the actual race scenes on the dirt tracks of New Jersey.

The picture was a hit and so were subsequent Dix pictures and then Famous Players moved to the west coast. La-Cava went along on a one-year contract and when that was up it wasn’t renewed.

He was an individualist. He didn’t fit in with a large organization. Sure, his work was all right but he wouldn’t take supervision. Anyhow, he tin-canned around for a year or two and then the pictures learned how to talk. He had never allowed himself to jell, to get set.

It was easy for him to adapt himself to talking pictures. He did a few of them for Pathé and he was all right too, but finally the supervision got too much for him and he exploded. He was having marital troubles that didn’t help any and he just didn’t feel like working. It was more fun to sit around with the boys hoisting a few and telling pleasant lies. He was healthy and full of animal vigor. He was lusty and strong and he’d take orders from no one. He didn’t know it but he was trying to get back at those kids in Towanda who had laughed at his father’s frock coat and at his curls. Months passed and people would ask, “Whatever became of LaCava?”

Then somebody told him about the psychiatrist. He went to see him and he found out that he was still annoyed at those kids who had laughed at his father.

It was Bill LeBaron who took the wild chance of hiring him just as he had hired him years before. LeBaron let him do a picture and it was all right. He let him do another and it was better than all right. He was on the comeback trail but it was a tough climb. He still wouldn’t take orders from producers; still wouldn’t follow a script he didn’t like. Walter Wanger (smart guy, Wanger) gave him a picture called Gabriel Over the White House to do. LaCava took the script, turned it inside out and started to work. They told Wanger he was crazy to let this madman handle a million-dollar production.

“Look at the rushes,” Wanger said to them calmly.

The rushes were great and the picture became one of the sensations of the film year. Now people started to talk about this LaCava who refused to compromise with anyone.

“He’s got something,” they admitted.

“If you let him alone he’ll make you a picture.”

Darryl Zanuck was starting Twentieth Century about now and he hired La-Cava to do Gallant Lady, starring Ann Harding. The Vine Street critics chuckled when they heard that.

“LaCava won’t last a week with Zanuck,” they said. “Zanuck won’t let a director change a line of script.”

LaCava knew this but nevertheless he read the script and threw it away. Each night he would write a few pages of dialogue and then in the morning he would give these sheets to the actors and say, “This is what you are going to say today.” For eight days he didn’t hear from Zanuck. So he kept right on making the picture. Then Zanuck started to send him notes, rave notes, saying that he liked the rushes. But Zanuck never appeared on his set. LaCava wanted to see him about something but the best he could do was to effect an exchange of notes.

His final note to Zanuck was, “If the picture is lousy, let’s shelve it and release the notes.

Go-as-You-Please Method

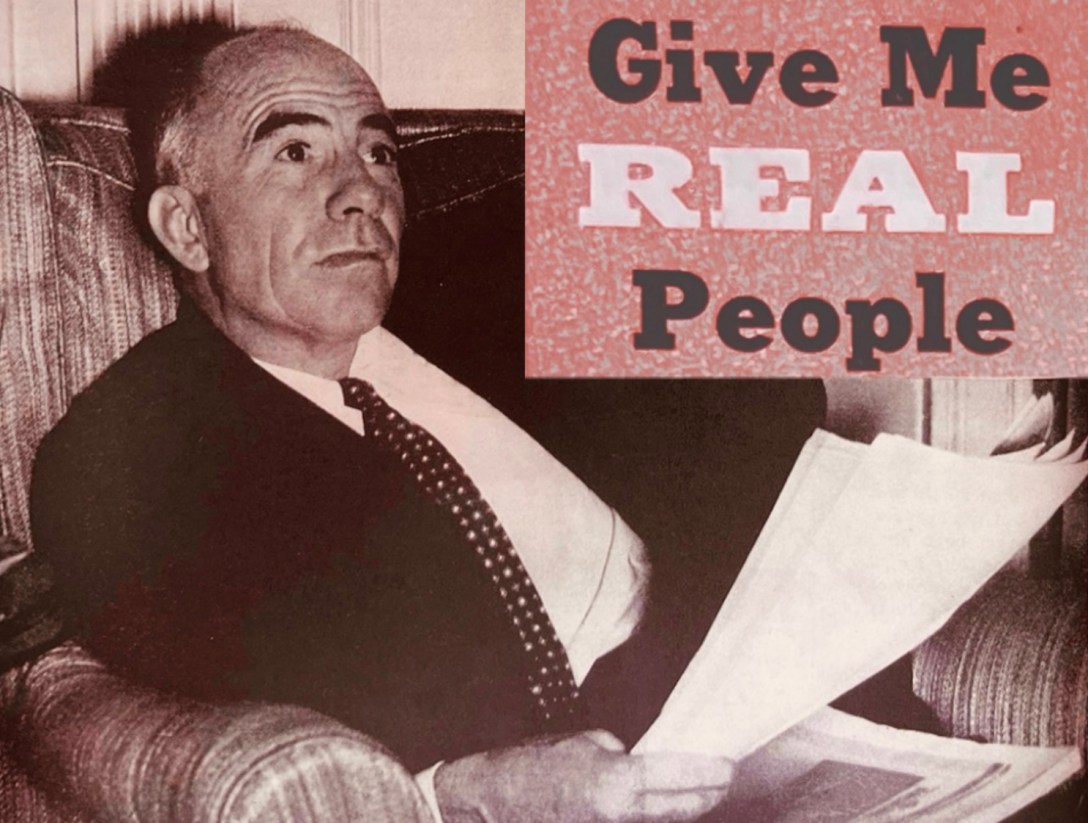

The picture was a hit. Everything he has made since has been a hit. His last two were My Man Godfrey and Stage Door, two terrific hits. They were “artistic,” though LaCava hates the word, and they were commercial. Today he and Frank Capra are recognized as the two greatest directors in Hollywood.

LaCava has a technique all his own. He uses what he calls a go-as-you-please method.

“I have no technique,” he says. “I have no formula. Give me a story about human behavior and I’ll put it on the screen. I won’t make a phony story. I don’t believe in phony stories or in phony actors. In fact, I don’t believe in phony directors. A director can’t make anyone act. A director can mine an actor, can get out of him whatever talent may lie hidden in him but he can’t make him act if he hasn’t got it.

“Give me real people to work with, people like Bill Powell and Carole Lombard, and we’ll give you a picture. Give me Hepburn, once you understand her, and give me a Ginger Rogers or an Adolphe Menjou, and we’ll give you a picture. They’re all real people, not dressed-up puppets. When I direct them I tell them to use their own personalities, not to assume someone else’s.”

Today LaCava is the highest-paid director in Hollywood. He makes only one picture a year. He isn’t hungry and he likes leisure. He likes to sit around with old friends in New York and hoist a few and tell and listen to pleasant lies. He likes to punch the bag with Grantland Rice or Damon Runyon or Rube Goldberg.

“They’re my kind of people,” he says. Well, they’re genuine, honest-to-goodness people whom success has never bothered. LaCava himself is like that. He’s one guy who’ll never go Hollywood.