I find La Cava’s work with Darryl F. Zanuck and the short-lived Hollywood independent studio Twentieth Century Pictures fascinating, hence this slight deviation in my narrative of blog posts. I will be finishing my piece regarding Gregory La Cava’s films in New York from 1920-24 soon, and discussing his time at Twentieth Century Pictures in more detail later, but I was just wonderfully surprised and very thankful for the AFI’s archivist Emily Wittenberg allowing me access to editor Barbara McLean’s Oral History interview.

A short overview before discussing La Cava and McLean’s work together, Twentieth Century Pictures was an independent production company established by Joseph M. Schneck, formerly president of United Artists, and Daryl F. Zanuck from Warner Bros, which merged in 1935 with Fox Studios to become 20th Century Fox. Despite its short-lived status as an independent studio, this kinda offshoot studio of United Artists (TCP films were distributed under UA) produced a fascinating collection of films between 1933-1935, and, according to Barbara McLean’s recollections, functioned in a similar way to United Artists. McLean worked as assistant editor on the United Artists’s Coquette (1929), where she worked closely with Mary Pickford, but in McLean’s recollections, however, she did not create a divide between the two companies in terms of management. McLean claimed that “it was like a family. It was so close-knit. When you worked for these independents, when you worked for Mary Pickford, it was a whole family.” McLean applied this to Twentieth Century Pictures, too, reiterating that “You loved them, and you wanted the picture to be great, and you didn’t mind how hard you worked. And that’s the faculty that Zanuck had.”1 Despite its collapse as an independent studio upon its merging with Fox, TCP boasted, and was entrusted by, directors such a Raoul Walsh, Richard Boleslawski, William A. Wellman, and strong independent spirits with the likes of Rowland Brown. There is little that ties these films together in terms of the work’s subject matter, apart from the number of period pieces, but there is a distinct individuality with the risks taken – such as with the opera film Metropolitan (1935), and The House of Rothschild (1934) to have three-strip Technicolor sequence.

La Cava and Raoul Walsh were two of the few directors actually signed to Zanuck’s new studio, and Walsh’s recollections of working under Twentieth Century Pictures on the company’s first film The Bowery (1933), which McLean also worked on as assistant editor, make it understandable why Joel McCrea was mistakenly lead to the conclusion that La Cava never worked for Zanuck.2

and Debra Weiner in 1974. From “Film Crazy”.

From the level of interference from script level upwards, La Cava making one picture let alone three with Zanuck is particularly amusing to picture. In a contemporary article by Quentin Reynolds for Collier’s, however, he claims that Zanuck’s interference on the set of Gallant Lady (1933) was restricted to passionate notes – of which La Cava reportedly responded with: “if the movie goes wrong, we can always premiere the notes.”3 Zanuck’s lack of presence on the film is particularly unusual, if the article is to be believed, and this could be due to this production company being in its infancy. McLean’s recollections of The Bowery follow similarly to Walsh, which I’ve shared extracts with below with courtesy from Emily Wittenberg of the American Film Institute. Interview with McLean conducted by Thomas R. Stempel from 1970-71 for the Darry F. Zanuck Research Project of the America Film Institute:

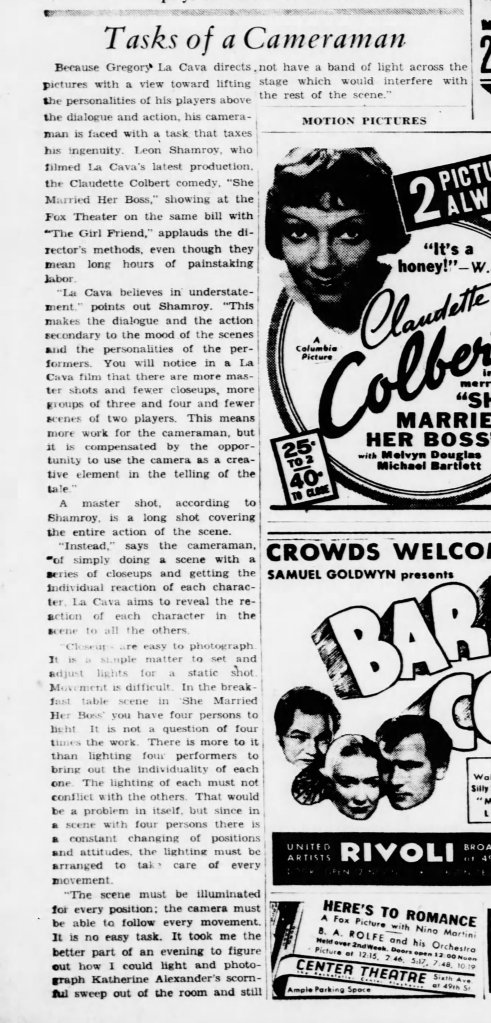

Barbara McLean first sole editing credit was on Gallant Lady, Gregory La Cava’s first of the two4 film with Twentieth Century Pictures, of which McLean celebrated with naming her boat after the film. Gallant Lady, to me, is one of La Cava’s finest works and elements of a great personal nature lay in the touches to Clive Brook’s character, such as with the nature of alcoholism takes on the less than liberating note than some of La Cava’s prior and proceeding work. McLean also took on La Cava’s particular idiosyncrasies regarding holding on the tendency to cut to close-ups, a wonderful example, which I recommend looking out for when watching Gallant Lady, regards a particular scene where Harding kisses Brook’s hand. La Cava’s tendency to hold on the close-up is a trait that cinematographer Leon Shamroy noted when working with La Cava on Private Worlds (1935) and She Married Her Boss (1935). McLean appeared to enjoy working with La Cava, and shares some kind words on working with him again on The Affairs of Cellini (1934). McLean also mentions here that she directed the close-ups herself, which is what reminded me of what cinematographer Leon Shamroy discussed in this article on his work with La Cava. La Cava not being as interested in close-ups as he was in the group response to the individual, and vice versa, is particularly fitting with his interest in the Depression and the class disparity. The article by Shamroy is taken from The Brooklyn Eagle, 13 October 1935.

Shamroy’s attention to what exactly is the distinctive quality of La Cava’s filmmaking beyond La Cava’s contribution to script and story is something that McLean indirectly touches on with regards to La Cava’s friendly nature and sensitiveness. The atmosphere he wanted to create was of one of naturalness and spontaneity; which required a cast and crew he trusted and vice versa, so it was not unusual for La Cava to work with the same editor, writer, cinematographer, and script supervisor more than once and more than just the happenstance of said crew and cast belonging to the particular studio La Cava was working under at the time. I will discuss his collaborations with Joel McCrea at another date, but La Cava’s trust and interest in McCrea against Paramount’s choice for the part in Private Worlds (1935)5 shows that he exercised what power he had to specifically choose the people he wanted to work with.

Unfortunately, so far, I have found little accounts from the actors who starred in Gallant Lady (1933) and The Affairs of Cellini (1934), but Fay Wray delightfully remembers La Cava in her memoir, On the Other Hand: A Life Story:

“We arrived in temperate California in time to begin The Affairs of Cellini. That film has a fine cast: Fredric March as Cellini, Constance Bennett as a duchess, Frank Morgan as her rather foolish duke. It was based on the play The Firebrand by Edwin Justus Mayer.

There was more than the average amount of waiting between scenes. Gregory La Cava, who directed, had a penchant for rewriting, for wanting to develop scenes peripheral to the script, to improvise, which he did at less than lightning speed. Constance Bennett had her own demands, which included being the first to leave the set each day. Louis Calhern, who played a nobleman, objected. When the film was presented at the Chinese theatre and all of us went, his speech to the audience ran: It had been a pleasure to work with (naming each in the cast), ending with “That is all”. He was satisfied, having pointedly left out Constance Bennett’s name. But I’m not sure the audience got the point. I heard no gasps.”

Wray’s comment on the improvisation further show that it was not selective films that feature La Cava’s interest in improvisation, but all his work holds that signature La Cava natural touch. Morris Ryskind also discusses the issues that La Cava had working with Bennett following Bed or Roses (1933), but is exactly that tempestuous personality that La Cava was drawn to and enjoyed capturing on film, as seen later when working with the cast of Stage Door (1937).

Finishing this blog post with some closing remarks from McLean on the directors she worked with. McLean points out the unfortunate early passing of directors such as La Cava and Richard Boleslawski, and it’s still fascinating to think of the number of great directors that worked under Twentieth Century Pictures during its short existence. I still believe a wonderful film screening (or streaming) programme could be made out of these films, partially as The Affairs of Cellini is such a joy and deserving of a large audience.

- Quotations from McLean are all from the 1970-71 Oral History Interview. By Thomas R. Stempel for the Darry F. Zanuck Research Project of the America Film Institute. ↩︎

- Joel McCrea in an interview by John Kobal, from Kobal’s book “People Will Talk”, p. 29:

↩︎

↩︎ - Quentin Reynolds, “Give Me Real People: Director La Cava’s Formula”, Collier’s, 26 March 1938. ↩︎

- La Cava worked on the story for Moulin Rouge (1934), but only worked extensively and directed both Gallant Lady and The Affairs of Cellini for Twentieth Century Pictures. ↩︎

- Joel McCrea discusses La Cava in his 1971 oral history interview by Charles Higham (https://dlc.library.columbia.edu/catalog/cul:zkh1893402). I have clipped and shared it on my Twitter account here: https://x.com/themoderns_/status/1873754859771678785 ↩︎

Heading image is of Barbara McLean in the editing room and Gregory La Cava with Ann Harding on the set of Gallant Lady (1933)